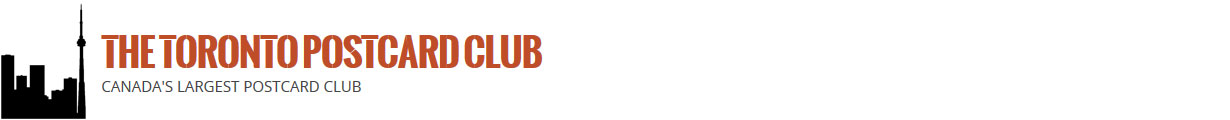

The Fall 2017 edition of the TPC magazine Card Talk is now out: our members should be receiving their copies in the next day or two. Because July 1st represented the 150th anniversary of Confederation (“Canada 150”), the issue has several articles of a “patriotic” nature, beginning with some reflections by veteran member Joe Rozdzilski on what Canada means to him as a son of immigrants who came to Toronto in the 1930s. Joe provided us with some illustrations, including a couple of lovely patriotic cards from Nerlich & Co. This design, which is embossed and beautifully printed, must surely be the single most elegant of the large and common series of lithographed Canadian cards published by the major manufacturers after the turn of the century. These Nerlich cards recall familiar Toronto scenes of the early 20th century — the corner of King and Yonge streets downtown and the busy (and very industrial) harbour.

Shields and Arms

The provincial shields on these cards are of some interest. Nova Scotia’s, at the extreme right, isn’t the familiar blue cross of St. Andrew on a white background, but the province’s older design centered – understandably enough – on a fish (salmon?). Also, because they are post-1905 (likely not by much), the cards show Alberta and Saskatchewan as provinces, but at this point Alberta was still using the shield of its predecessor – the North West Territory – which featured a polar bear (rare in Alberta!) over four sheaves of wheat. Saskatchewan was apparently more on the ball, as it had already come up with its own exclusive design, featuring a more modest three sheaves of wheat.

Curiously, the coat of arms depicted at lower left is not that of Canada but rather the United Kingdom’s coat of arms (which was of course that of King Edward VII, who was also King of Canada – so not at all inappropriate).

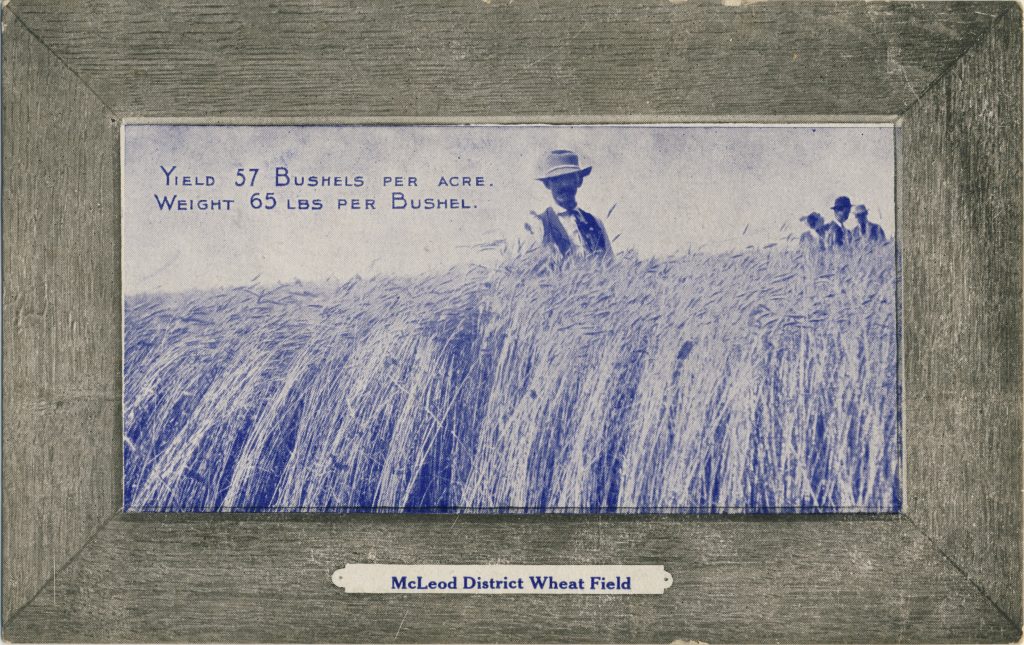

Granary of the World

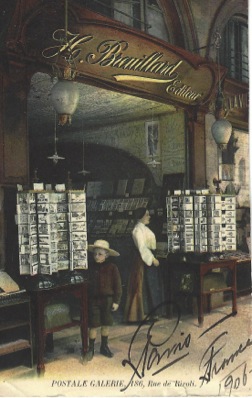

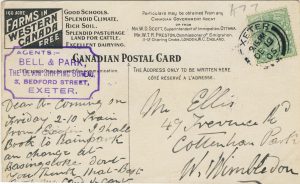

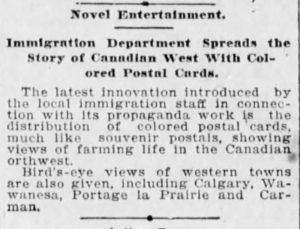

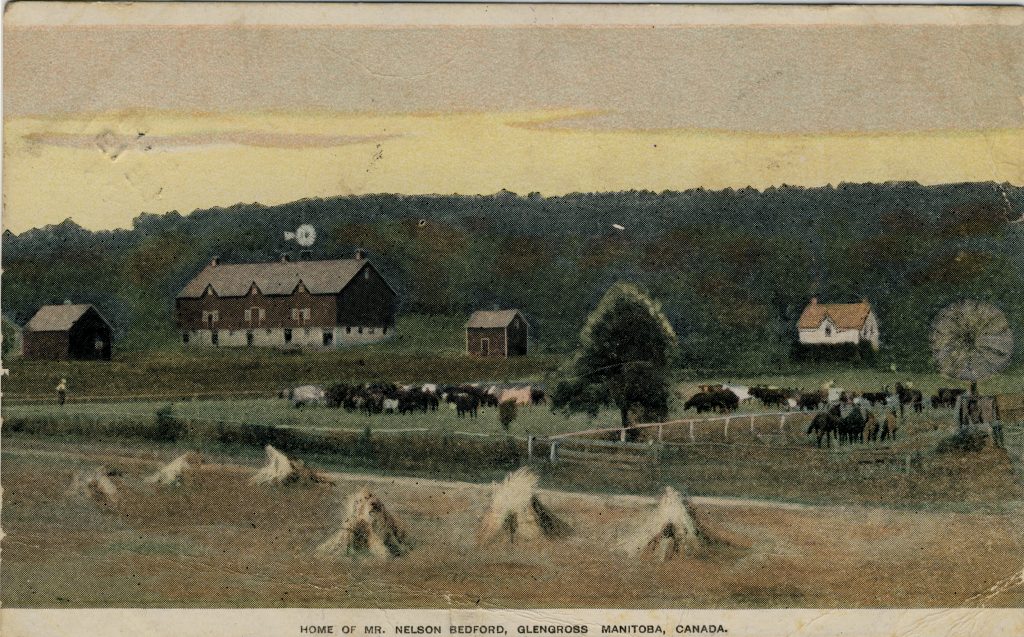

Also (partly) on a Canada-Britain theme, Barb Henderson has contributed an article on postcards with the theme “Granary of the World”, “Britain’s Granary” or the “Granary of the Empire” … that sort of thing. Among these are several of the ceremonial arch that the Dominion government erected in London in 1902 at the time of Edward VII’s coronation. There is also a fine example (see below) from the well-known series of twelve postcards issued (seemingly) by the federal government around 1906 to encourage immigration from the U.S. The illustrations on these cards originally appeared in a pamphlet published in 1903 by the Interior ministry of Sir Clifford Sifton.

Repatriation of Lost Treasures

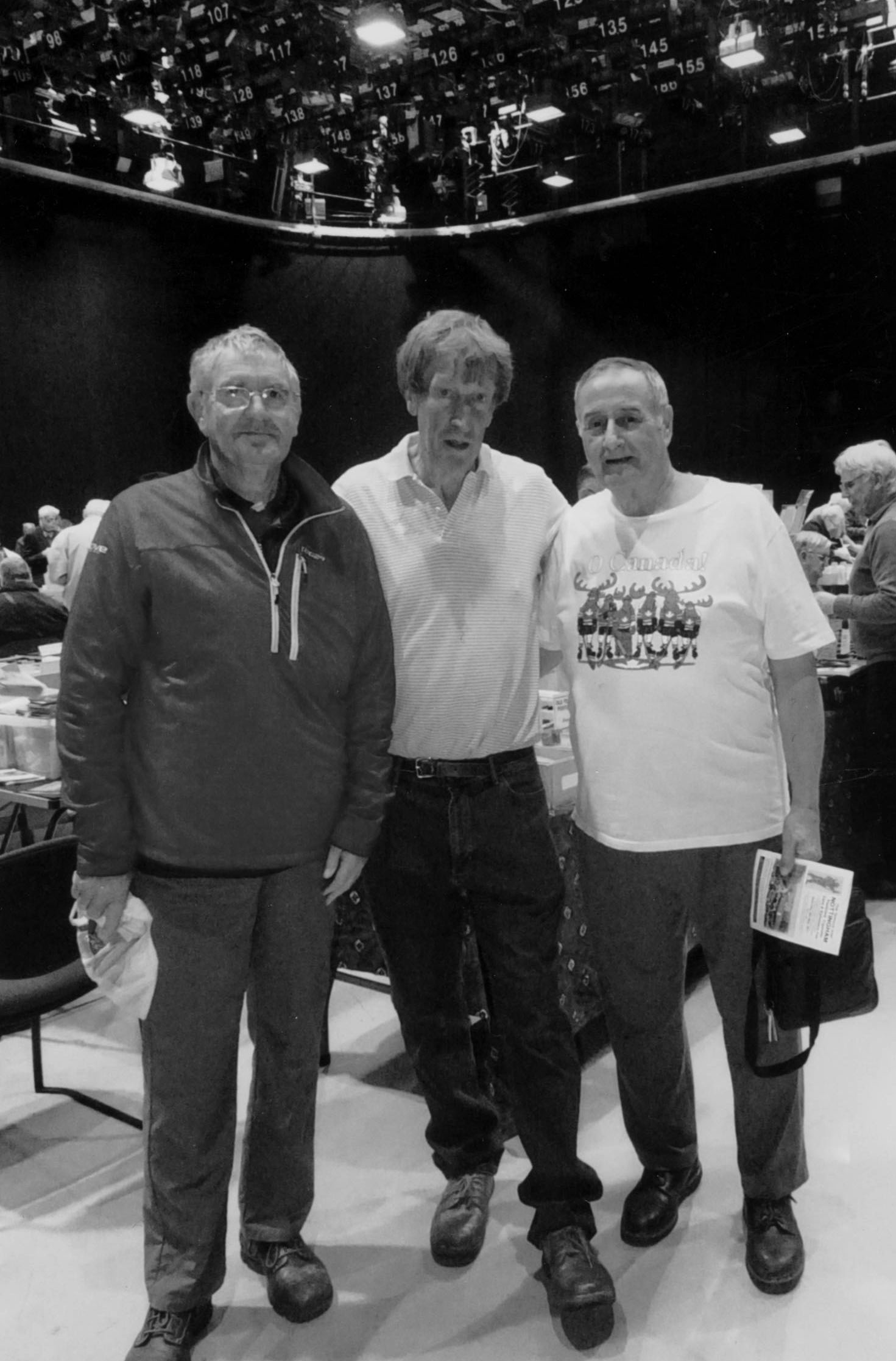

In another article, long-time member Bob Atkinson writes of his latest travels to postcard shows far and wide. This time his journeys took him to Vancouver and Nottingham, where he met organizer Brian Lund, for many years publisher (with his wife Mary) of the British periodical Picture Postcard Monthly and still at work on the Picture Postcard Annual. As usual, Bob was on the lookout for hidden Canadian treasures and (having forewarned dealers to his visit) came back with quite a handful. Below is a photo of Bob (at right) with his English cousin Malcolm Henderson and Mr. Lund in the middle.

Malcolm Henderson, Brian Lund and Bob Atkinson at the Nottingham (U.K.) show. (courtesy R. Atkinson)

Theatre Cards from New York City

In not-specifically-Canadian news, we have accounts of some of our club talks, including Kyle Jolliffe’s “Broadway Ballyhoo”, an examination of New York City theatre postcards from 1900 to 1916. Kyle’s many postcards include the Korean comic opera “The Sho-Gun”. Many of the cards were produced by the Rotograph Co. as publicity for upcoming shows. Kyle, who focuses on New York postcards, also highlighted rarely-seen sets of Canadian cards by Warwick Bros. & Rutter – the “Celebrated Actor” series, which featured 36 or 37 cards – and by W. G. MacFarlane, who used Rotograph images in another hard-to-find series of cards.

And Much More…

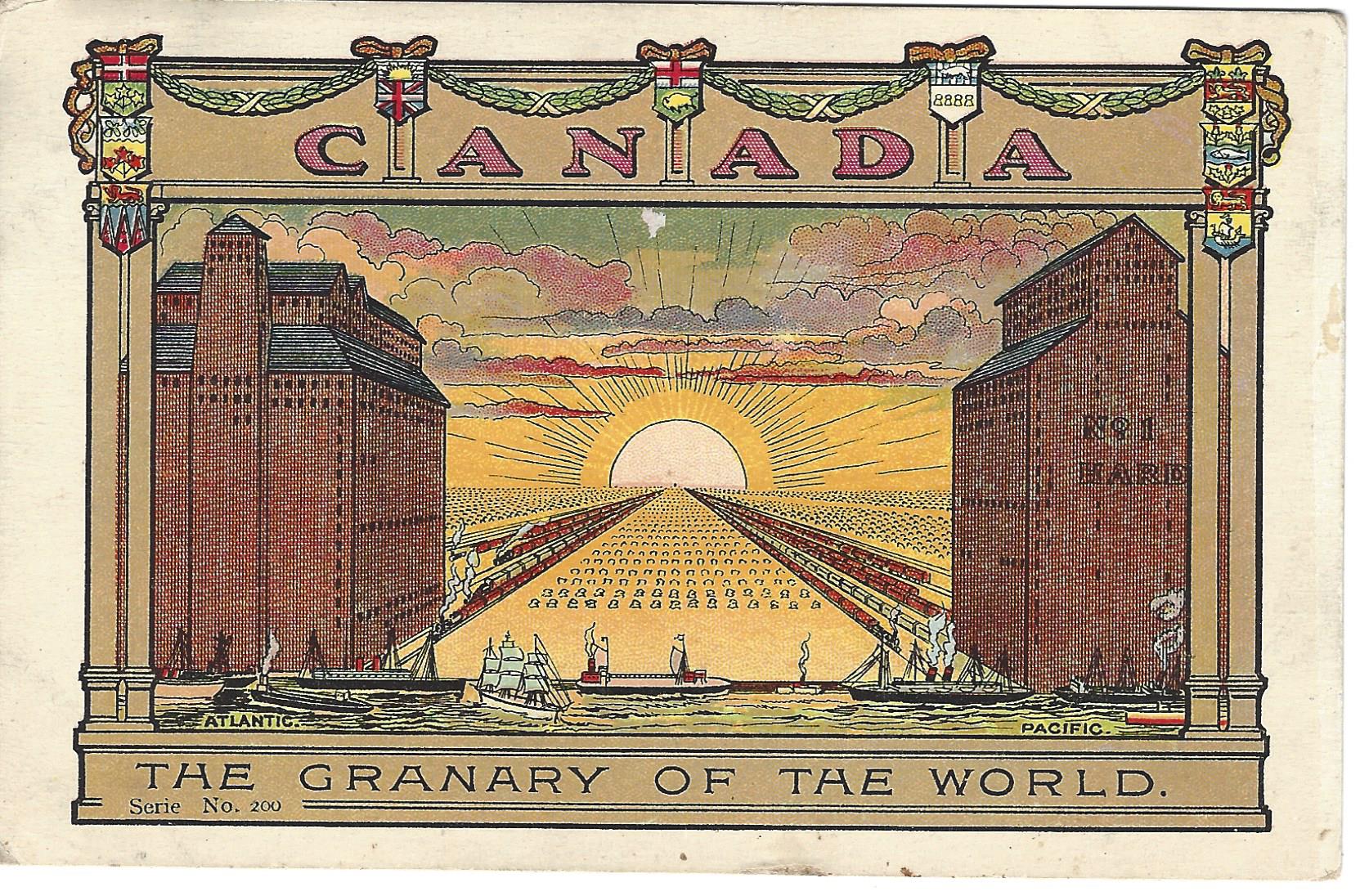

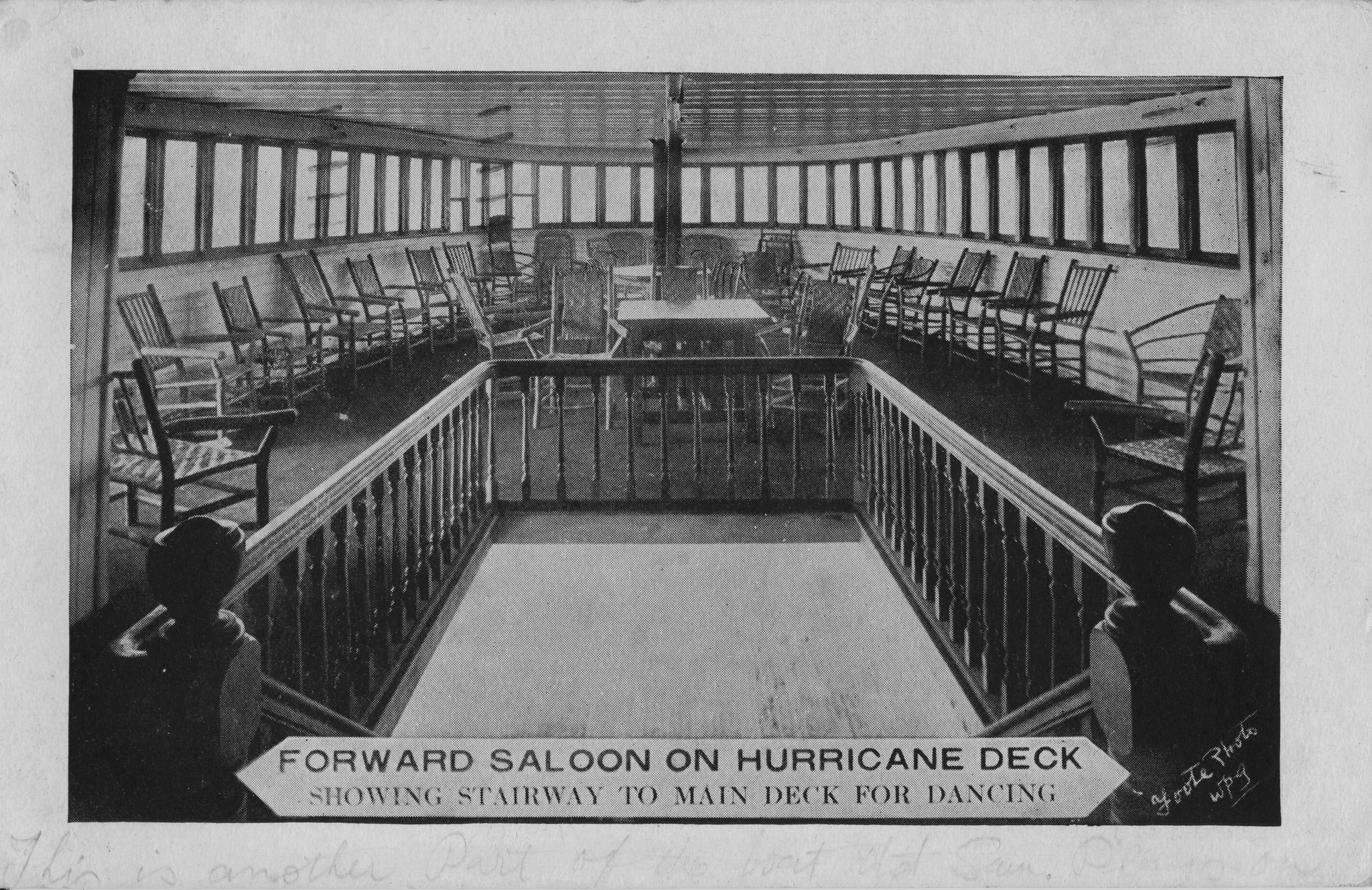

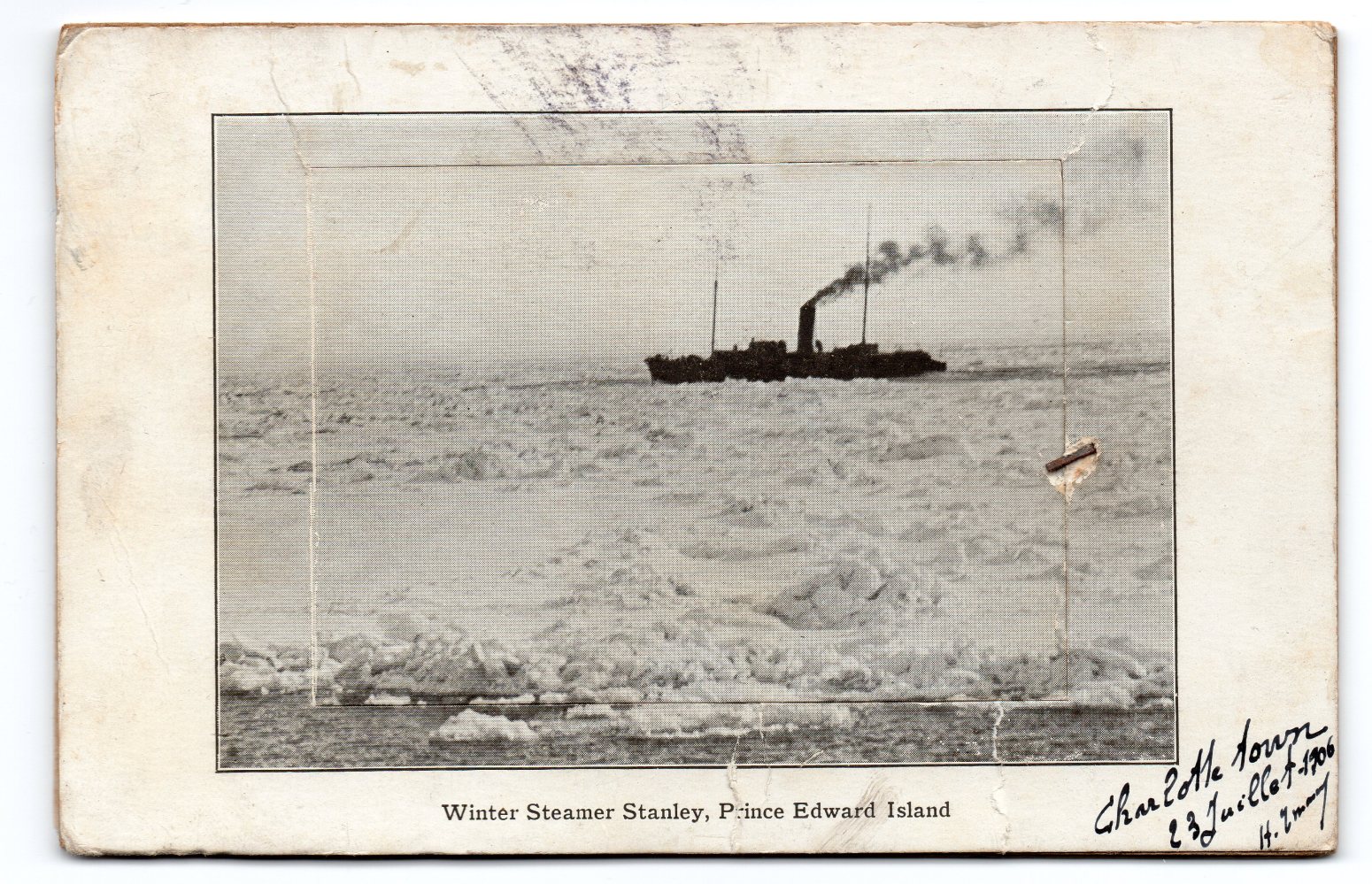

Other articles recount a talk by Ralph Beaumont – author of Heckman’s Canadian Pacific, an outstanding volume of early 20th century railway images not no Canadian history buff (or railway buff) should be without – and our own Mike Smith’s talk on his (and Larry Mohring’s) equally fascinating volume on the Canadian photographer Reuben Sallows, whose photographs were used on hundreds of Canadian postcards illustrating “scenes from ordinary life” in the young country of 1900-1910, in addition to numerous covers of the Canadian magazine Rod & Gun and illustrations in many U.S. periodicals of the day as well. Mike’s book may be ordered here.

John Sayers contributed articles on the ongoing TPC auction and the Canadian National Exhibition, while Andrew Cunningham added an article about the use of Esperanto in postcards and postcard exchanges.

Join Us!

As always, we conclude by noting that Card Talk is not available on newsstands – it’s only to be had by joining our Club (or, I suppose, by craftily befriending someone who already is … but in that case why not join anyway and stop being such a mooch?!) Sign-up details are available here. We hope everyone had a happy “Canada 150”!

(By Andrew Cunningham)

![[WW I butterfly silk]](https://torontopostcardclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/WW-I-butterfly-silk-1024x659.jpg)

![Home of Mr. Nelson Bedford, Glengross, Manitoba, Canada [back]](https://torontopostcardclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Home-of-Mr.-Nelson-Bedford-Glengross-Manitoba-Canada-back-1024x628.jpg)