1. What is the VALUE of my POSTCARD collection?

1. What is the VALUE of my POSTCARD collection?

The best way to determine valuations is to go to a postcard or paper show, such as the TPC’s annual sale, where you can review the retail prices of similar postcards. If your postcards are for sale, dealers in attendance might make you an offer. Our show calendar has a list of upcoming shows in Ontario. Often there are postcard sellers at antique and stamp shows. Two websites where you can find such events listed are Wayback Times (for Ontario collectibles shows) and Canadian Stamp News.

The value of vintage postcards is essentially determined by the purchaser. Unlike coins, stamps or sports cards, there are generally no ‘catalogue’ valuations. Postcard dealers set retail prices based on the age, subject, type and condition of a postcard. A dealer’s buying price reflects their business parameters, current inventory and how quickly the postcard might be sold. When offering to sell postcards to dealers, expect no more than 50% of the retail value as a possible offer, and potentially much less depending on the condition, age and subject matter. With some exceptions, postcards of foreign subjects do not sell well in Canada, and it’s better to seek a foreign buyer for a collection of such cards.

Are there typical price ranges for postcards?

At a postcard show you can usually purchase postcards at prices ranging from $1.00 for ordinary postcards from the 1950s and later, to $100.00 or more for unique and special earlier ones. Lithographed postcards from the early 1900s are often priced from $3.00 to $10.00. Postcards from 1930s and 1940s are priced similarly. Most cards from the 1950s and later, particularly “chrome” cards showing common tourist scenes in Europe, large North American cities and tourist areas, national parks, etc., are currently worth very little. That said, some of these ‘modern cards’ are beginning to be sought after so prices for these are rising. In this category are those depicting social history, classic tourist themes such as older Walt Disney, motels, vintage cars, etc. In general, if your postcards are less than 75 years old and show typical sightseeing locations, be prepared for the possibility that they will attract minimal, if any, offers. There are exceptions, of course!

Tip: To get an idea of the value of your postcard, check recent prices on eBay (‘sold’ prices can be accessed via eBay’s advanced search) or other similar sites such as Delcampe or Hippostcard. Simply type in the caption on the card, or its subject, and in many cases one or more instances of your exact card can be found.

What factors affect the value of a postcard?

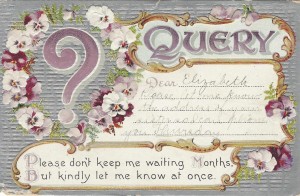

Worn, broken corners and creases reduce the value and some purists balk if there is writing on the view side. There are others who prefer the writing as it may reveal some interesting information, or the date of use. Early 20th century postcard views that would have been abundant (of a big city like Toronto, for example) tend to be less expensive than those of a smaller town. However, as many collectors are looking for specific publishers, photographers, artists or design types, postal history (e.g. the stamp or cancellation), or special messages, a postcard with an uninteresting view might be desirable to these collectors regardless. Older and rarer postcards, even in poor condition may command a higher price, especially if they carry an interesting ‘in period’ message. Postcards with a special feature such as an advertising message, a novelty appliqué, mechanical component or other unusual aspect of construction are worth more than similar cards that without these attributes. Some of the most sought after subjects include small-towns, train stations, postcards of disasters, political or social events, and postcards depicting sporting events. Only a minority of any ‘better’ postcards command unusually high prices due to their scarcity or the topic of the image.

Are photo postcards more valuable than other kinds?

Real Photo Postcards (RPPCs) are among the cards that North American collectors value most highly. Other geographies may value other styles, for example early ‘Grus aus’ postcards in Europe. Because the RPPC heyday was from around 1904-13 when western Canada and the USA were being settled, and eastern regions developed, RPPCs are particularly valued for their important visual record of an important formative period of pioneer and agricultural life, and industrial expansion, for example.

What were they? As the name suggests, RPPCs were ‘real photographs’ that were developed directly on postcard paper, often supplied by Kodak under brand names such as ‘Velox’ and ‘AZO’. Many RPPC images are rare or possibly unique, as these postcards were usually made in small numbers by amateurs, local photographers and often by itinerant photographers who toured towns and villages. The subjects of RPPCs are almost infinite profiling every aspect of local life: people, houses, shop windows, churches, schools, parades, celebrations, disasters, royal visits, sporting matches, and almost anything else you could imagine.

As with any other postcard, if an image is dull, poorly framed or in poor condition, being an RPPC won’t redeem it. The most valuable era of RPPCs is unquestionably the ‘Golden Age’: early 1900s-1919. Note that mechanically produced photo cards, such as those published in large quantities by Rotograph or Rotary Photo, Gowen Sutton in Canada, are generally not in the same league as ‘real’ RPPCs made one-at-a-time in darkrooms by RPPC photographers.

RPPC prices can range from around $5 to over $100, with some exceptional cards selling for many hundreds of dollars. For example, an RPPC that features members of a Stanley Cup finalist team from the pre-NHL era, might command a 4 figure price. Generally speaking, you can expect to pay between $15 and $50 for an attractive and interesting small-town view.

2. What should I do with an INHERITED BOX OF OLD POSTCARDS?

Selling to a collector or dealer is a possibility, as discussed (1) above. Alternately, you could consider donating them to libraries, museums, historical societies or educational institutions. Another possibility is to gift them to a seniors’ residence or care home, where they may used in cognitive therapy or crafting programs. Postcards with stamps of any era and geography are welcomed by the charity ‘OXFAM CANADA STAMP ‘ program. Whatever you do, PLEASE DO NOT TOSS OLD POSTCARDS! Find them a good home. If you’re stuck, contact us or any other stamp or postcard club in your area. We can’t always help but we’ll try.

For larger or more valuable collections you might wish to consider a major archive, university or similar institution. To understand some of the issues involved, we highly recommend this presentation from a joint meeting of the San Jose Postcard Club, Wichita Postcard Club, Toronto Postcard Club (and others) held in April 2024.

3. Where do I purchase ALBUMS, SLEEVES and ALBUM PAGES for my POSTCARDS?

CANADA

Ontario – Select sizes only. Contact Robin at nsaauctions.com

Ontario – Coin and Stamp Supplies website

Online, from common sources such as Amazon.ca or eBay.ca

USA

BCW Supplies website

Mary Martin Postcards website

Online, from common sources such as Amazon.com or eBay.com

4. What is the EARLY HISTORY of postcards?

In 1865, at the Austro-German Postal Conference, a proposal for an ‘open post-sheet’ was made by German postal director Heinrich von Stephan. It was soundly rejected. In 1869, Dr. Emanuel Herrmann, an economist in Vienna, brought a variation on the idea forward, suggesting a ‘correspondence card’ (Correspondenz Karte) that could be posted at half of the usual letter rate, provided that any message added by the sender did not exceed 20 words. Herrmann successfully convinced Austrian postal authorities that permitting these short communications, which would often be of a commercial nature (acknowledgements, advertisements of services, etc.), would be more efficient and economical — in his view, any lost revenue from letter-post would be made up by the greater volume of these new government-issued correspondence cards (now often referred to as ‘postal cards’). As a result, postcards (in this early form) became an officially recognized category of mail on October 1, 1869 in Austria. It was reported that 3 million were sold in Austria-Hungary in 3 months.

In subsequent years, many other countries amended their domestic postal regulations to permit the use of ‘postal cards’. Costing half the letter rate, they were government issued and pre-printed with stamps — privately produced postcards were not allowed. One side was exclusively for the address, the other side was left blank for written communication. Initially, there were no illustrations or images on these cards but in time, users such as businesses, added their own illustrations to the blank side.

‘Postals’ came into use in: Germany, July 1870, United Kingdom, October 1870, Canada — the first non-European country — on June 1, 1871, and various other countries from 1871-73. The U.S. Congress passed the necessary regulations on June 8, 1872 but the U.S. post office did not actually begin to sell their postal cards until May 12, 1873 (in Springfield, MA). On July 1, 1875, agreement was reached at the first International Postal Congress allowing the exchange of ‘postal cards’ among the 22 (mostly European) member countries.

The ‘picture postcard’ with its ‘divided back’ for both the message and address was another 25 or so years in the making, although postal cards with added vignettes and scenic views were not uncommon in Germany from the 1870s onward. Postal cards issued in connection with the Chicago World’s Fair (Columbian Exposition) of 1893 are suggested as the first of this type in the U.S., and their popularity may have contributed to the growth of view cards in North America, particularly when non-government ‘private postcards’ became allowed.

On December 29, 1894, the government of Mackenzie Bowell, 5th Prime Minister of Canada, authorized private postcards in Canada. By the summer of 1895, these were used by businesses, largely for commercial purposes and were in broad circulation. It should be noted that a loophole in Canadian postal regulations, had technically allowed private post cards for a few years in the 1870s, although only a handful of cards from that era are known to exist today. The private postcards authorized in 1894 differed from the older postal cards in several respects: they were issued by private parties rather than the post office, they could be somewhat larger in size than the ‘government postals’ and (not being official ‘postal stationery’) they did not bear a pre-printed stamp. It was not until 1898 that postal authorities in the U.S. authorized ‘private mailing cards’ for that country. The private postcards of this era are sometimes referred to as ‘pioneer postcards’. In the North American context, generally, this description applies to postcards until around 1901 at the end of the Victorian Age (although it should be noted that there are other interpretations of the ‘pioneer’ era).

These ‘private mailing cards’ (U.S. term) or ‘private post cards’ (Canadian term) initially had ‘undivided backs’ — because of regulations that required one side of a post card to be used for the address only, and the other side for the message. Between 1902 and 1907, members of the Universal Postal Union (UPU) successively relaxed their regulations to permit the back of a post card to be ‘divided’. Now, both the address and a message were allowed on one side of the card, which were ‘divided’ by a vertical line. This left the other side entirely free for images, artwork, or any other visual component. In Canada, this regulatory change took effect on December 18, 1903. In practice, the market was slow to catch on and it wasn’t until around 1905 that ‘divided-back’ postcards replaced undivided-back cards in Canada. Once divided-backs had been adopted by all UPU members — Japan and the U.S. were the last major countries to do so, in 1907 — the postcard had taken on the form that we know today. The era from approximately 1901-1919 is often known as the ‘Golden Age’ of postcards (again, there are other interpretations of the exact boundaries of the ‘Golden Age’).

This blog relates this chronology simply and with some illustrations.

After 1919, postcard usage remained relatively popular, but the culture of collecting died down, as did the number of postcard manufacturers. The inventiveness and artistry of the ‘Golden Age’ were replaced by mostly typical views of lesser quality. As well, other social activities and entertainments had emerged making postcard collecting less interesting. New alternatives like French-fold greeting cards as well as the more widespread use of the telephone obviated some of the prior use of postcards, leaving them to function primarily as tourist souvenirs, which is how many of us know them.