Our annual Seasonal Party this past week was a great success. In addition to delicious food, the TPC served up the latest edition of Card Talk to all attendees, thus saving some postage costs. Retrieved from the printers only hours earlier, the Winter edition of our flagship (well … only) publication contains its usual 24 pages of deltiological news and analysis.

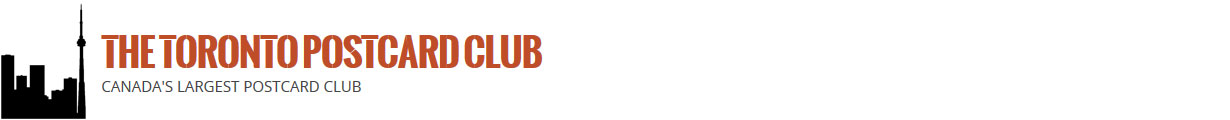

Following up on an article in the Fall edition, TPC member Lorne Smith contributed additional information on the use of Esperanto in postcards, including an account of his visit to the Esperanto Museum in Vienna. Among the postcards in Lorne’s collection is one of Prague’s Old Town Bridge Tower (Figure 1), with a message in esperanto and an Esperanto sticker on the front. The postcard’s caption has also been translated by the sender.

We had a response to our call for early Canadian RPPCs (real photo post cards) — “early” being 1904 or prior. Member Rick Parama submitted a photo card of a cow and calf from Bowden, Alberta, N.W.T. (as it then was) from the summer of 1904. Generally speaking, RPPC production in Canada seems to have gone from almost nil in the spring of 1904 to a significant trickle in the later months of 1904. By mid-1905, it was a veritable torrent that did not die down for several years thereafter. Real photo cards from 1904 and earlier are rare in Canada and we continue to solicit members and the general public for examples to illustrate the early days of this important photographic genre.

Another of our members, Joe Rozdzilski, contributed some examples from his collection of west-end Toronto postcards, focusing on the life and times of Sunnyside Beach and its amusement park and bathing pavilion, the latter of which could accommodate 2,000 swimmers and was, on opening in 1922 (Figure 2), the largest heated outdoor pool in the British Empire. The amusement park was a wonderland of food and attractions that are brought vividly to life in Joe’s story.

In 2016, we discussed the postcard photographer Lewis Rice, who worked first in his native Nova Scotia but more famously, after around 1907, in Saskatchewan, where he carried on business in the boom town of Moose Jaw. In this issue of Card Talk, the TPC’s Barb Henderson and Vancouver Postcard Club’s Gray Scrimgeour recount the events of June 1, 1912, which was declared to be “Postcard Day” in Moose Jaw. This was a Board of Trade effort to promote the new city by having its citizens send out Lewis Rice postcards with pre-printed boasts on the back. Through years of diligent searching, and with the help of fellow collector Don Kaye, Gray has found cards bearing nine different slogans, such as:

- FIFTY THOUSAND more CITIZENS WANTED who are law abiding and can stand prosperity for it’s sure to get you if you come to MOOSE JAW.

- Some towns are afraid to see new people come in, fearing that there will not be enough for all. That’s not Moose Jaw.

- Welcome Nobles [i.e. the Duke of Connaught and his family] to Moose Jaw — the Minneapolis of Canada.

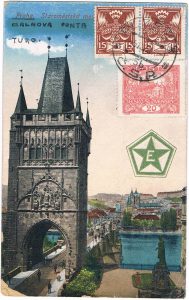

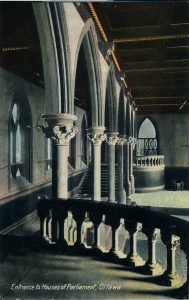

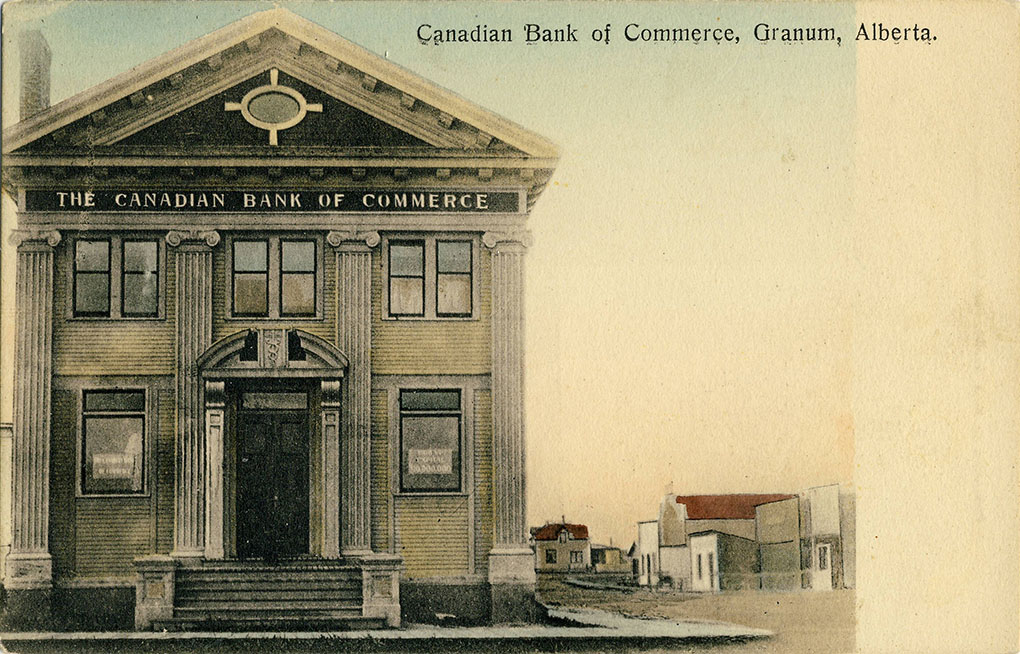

This edition’s cover story shows some of the many ways in which postcards take us inside Canadian buildings of the early 20th century. From the old Centre Block of Parliament (Figure 3) to the elegant Vice-Royal Suite of Winnipeg’s Royal Alexandra Hotel (Figure 4) to the interior of the ill-fated Great Lakes passenger vessel Noronic (Figure 5), postcards offer views of interiors that are invaluable to our understanding of the history of everyday life as experienced in ordinary houses, grocery stores, hotels, restaurants and factories.

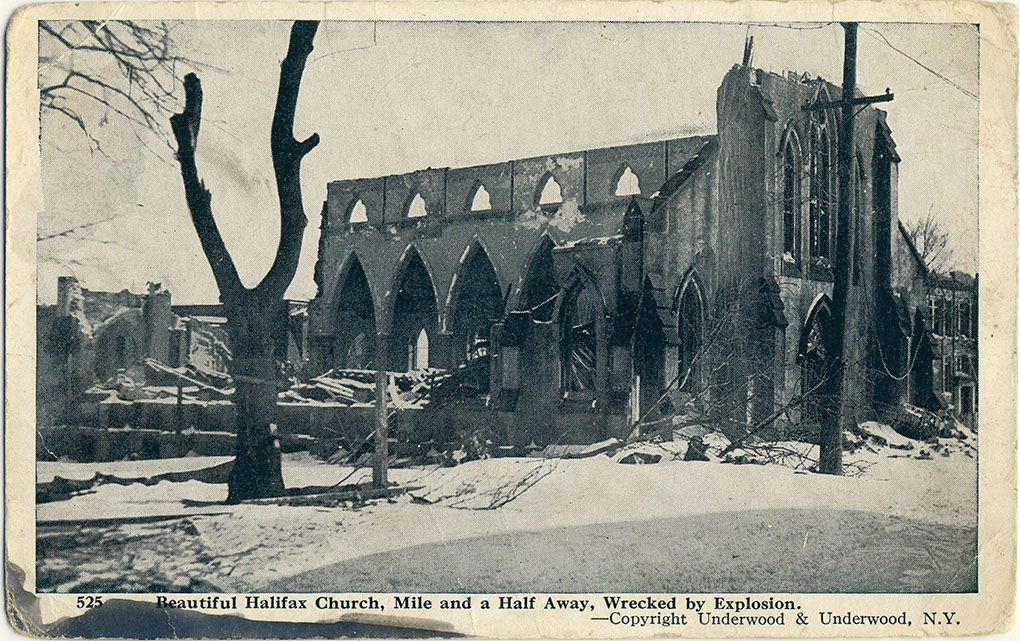

An item of special interest in this issue is a checklist of Halifax Explosion postcards, compiled by our member Terry Robbins and included in Card Talk in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of that tragic event — the most devastating man-made explosion in history prior to the atom bomb. Lithographic cards by Cox Bros., H. H. Marshall and Novelty Manufacturing & Art Co. are included in the listing. In addition, Barb Henderson has contributed articles on an amazing postcard relating to the aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss and on pyrography, the art by which leather postcards — including the example shown in Figure 6 — were created.

In addition, there are the usual features: a message from our President, reminiscences about Card Talks past (1982 this time), advertisements from our advertisers, our TPC meeting schedule and the round-up of upcoming postcard sales and shows. If you’re not already a member of the TPC, join our coast-to-coast (and U.S. and overseas!) membership and receive the whole Card Talk story three times annually, attend our informative (yet fun!) meetings and get special deals on our show admission and our exclusive members-only auctions.

(Andrew Cunningham, editor)

![[WW I butterfly silk]](https://torontopostcardclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/WW-I-butterfly-silk-1024x659.jpg)