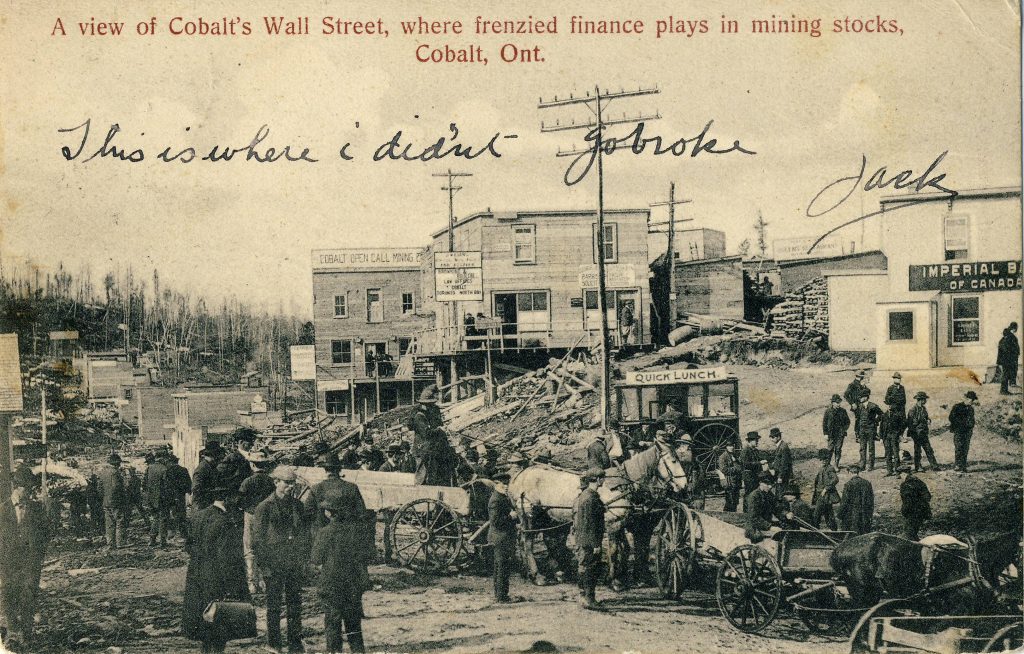

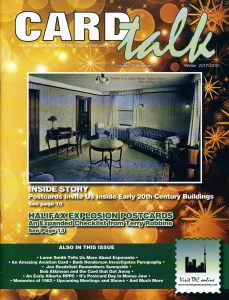

Many books on postcard themes have titles that include the phrase “Wishing You Were Here”, undoubtedly chosen because those four words evoke postcards as much or more than any others. And yet, as other collectors may also have noticed, the classic clichéd postcard message — which in its fullest form runs, “Having a good time. Wish you were here”– is actually not found with any frequency on old postcards. Truth to tell, I’ve never seen those exact words, even once, among the thousands and thousands of postcard messages that I’ve seen. That’s not to say that I don’t have a few postcards with variations on the “Wish you were here” part, but I’ve never seen anything approaching the whole thing.

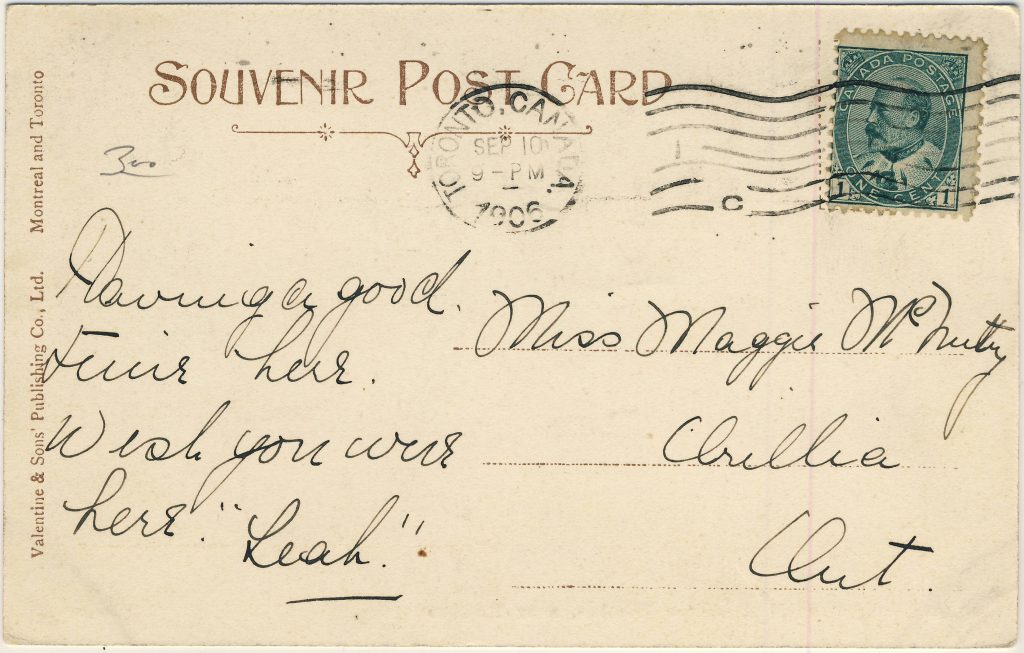

My longstanding conclusion, so far as I’d given the matter any thought, had been that “Having a good time. Wish you were here” must have become a go-to message for hurried postcardists well after the Golden Age (pre-1920) period that is the focus of my and many other collections. Well, I’m pleased to be able to say that that analysis might not be entirely true — it appears that I gave up too soon. On the reverse of a recently acquired (and very early) Canadian Valentine & Sons card — “A Young Enthusiast on the Humber, near Toronto” (no. 100,111) — there is, lo and behold, this simple message from “Leah”, written in the late summer of the year 1906:

Having a good time here. Wish you were here.

But for the first “here”, my prayers would have been entirely and perfectly answered, but (not being a fussy type) I think I can still declare victory. The greatest cliché in postcard history can in fact be traced to the earliest years of the fad. The mysterious “Leah”, who tantalizingly enveloped her own uncommon name in mysterious quotation marks, thus enters the ranks of the deltiological immortals.

The elusive message, finally found (almost!). Did Miss Maggie McNulty appreciate the significance of what she’d received? Did Leah’s sentiment sound fresh and clever to her, rather than hackneyed? Wish we were there to find out!

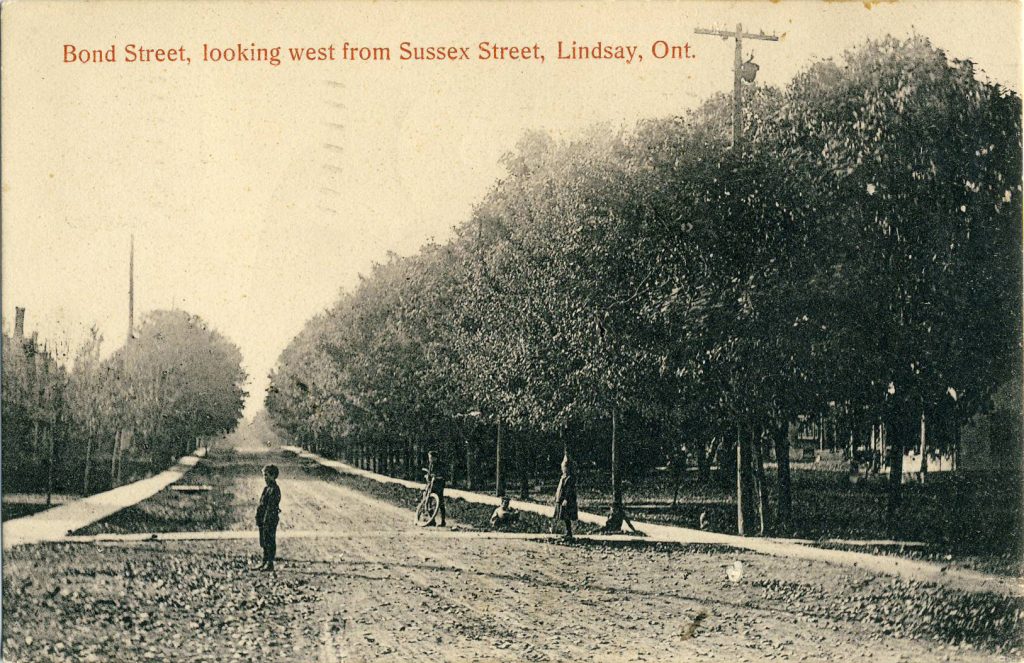

The postcard image is worth noting in its own right. It’s a charming example of an uncommon early style of Valentine & Sons postcards — a simple, uncoloured collotype.

Early 20th century writing styles and conventions, as commonly seen on postcards

That brings to mind a question about what we learn from the letters on early twentieth century postcards, in general — not from the content of the messages themselves, but from the handwriting, spelling, grammar, forms of address and so on. Here are a few examples that I’ve noticed over the years:

- The very common use of the colon-dash (or maybe colon-hyphen) after the salutation, as “Dear Maggie :-” — this has totally disappeared but must have been a staple of children’s lessons around the turn of the 20th century;

- The tendency to omit punctuation almost entirely from brief messages. This is not simply a function of being poorly educated: punctuation is often lacking even in notes penned by writers who spelled well and were clearly men or women of some sophistication. Commas were barely used and anything more esoteric than that — even a question mark — was quite unusual (as was the use of paragraphs);

- It’s unusual for there to be even a P.O. box number in small-town addresses until around 1910 or after – almost always did the name of the town suffice;

- On the odd occasion that we still write letters, and also in emails, we often write “Dear Mom” and “Dear Dad” — but in the Golden Age days it was equally common to include lateral relationships like “Sister” or “Aunt” in the salutation in exactly the same way, without appending the addressee’s given name. Other than for direct forebears (parents and grandparents), we have lost that reluctance to “first-name” people;

- Grown children sometimes signed letters to their parents in a rather formal fashion, using their full first and last names, which would seem odd to us today.

What other bygone conventions have you noticed in postcard letters? We’d be glad to get your examples and/or to hear about any other early examples of postcard messages that say “Having a good time; wish you were here”, or something close to it.

(Andrew Cunningham)