By Andrew Cunningham

Winter is nearly here … the “Winter” edition of Card Talk, I mean. The Toronto Postcard Club’s 24-page magazine is currently in the mail to its millions, thousands, hundreds of eager readers from coast to coast and (in a few cases) beyond our coasts in faraway lands such as the U.S.A. As is customary, the blog will provide a short summary of this edition’s articles in order to alert the entire planet to our content and (hopefully) to entice one or two postcard enthusiasts to join our club.

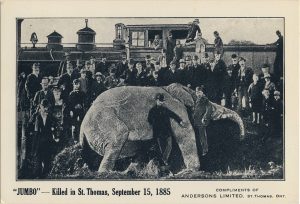

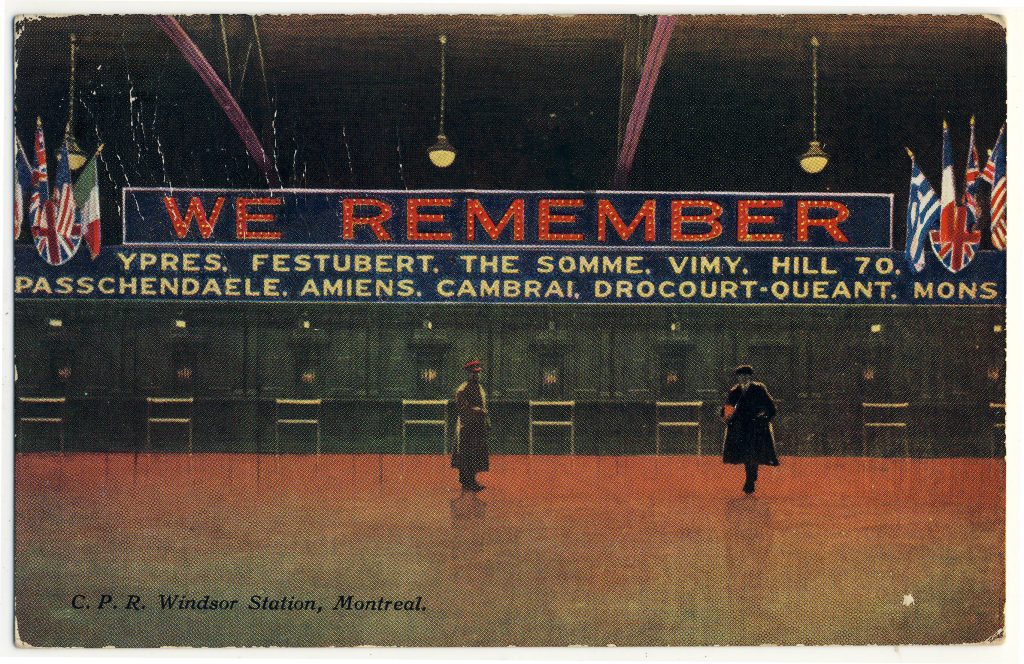

The cover story this issue is a tribute to elephants. Specifically, your editor has written an article based on postcards of elephants plying their trade (as circus entertainers) in Canada. While we think of ourselves as highly cosmopolitan today, the fact remains that, thanks to the circuses that criss-crossed the country every summer, our Edwardian ancestors were far more familiar than we are with the exotic pachyderm. In the article, there is naturally some discussion of circus history, which is illustrated by postcard examples such as the pre-performance parade by the Adam Forepaugh & Sells Bros. circus shown here [1]. The Forepaugh & Sells circus was visiting Portage la Prairie, Man., in the summer of 1911 (their last year in the business, it happens). Posters advertising the event (including a large one depicting the elephants) may be seen in the image, which is a small detail of a much larger real photo postcard.

[1] Portage la Prairie townsfolk watch the Forepaugh & Sells circus parade, 1911 (RPPC detail)

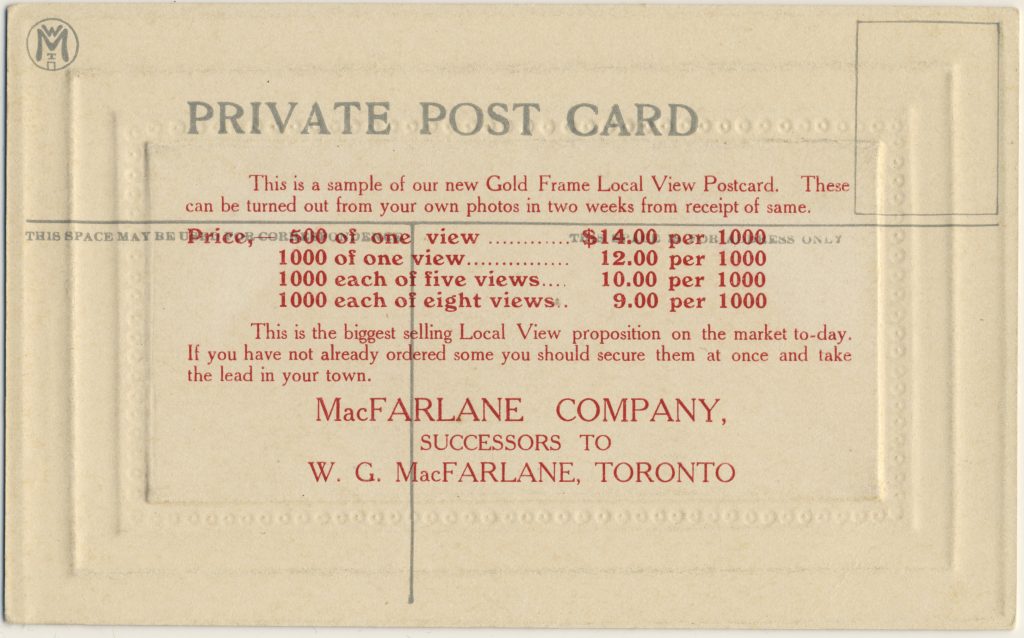

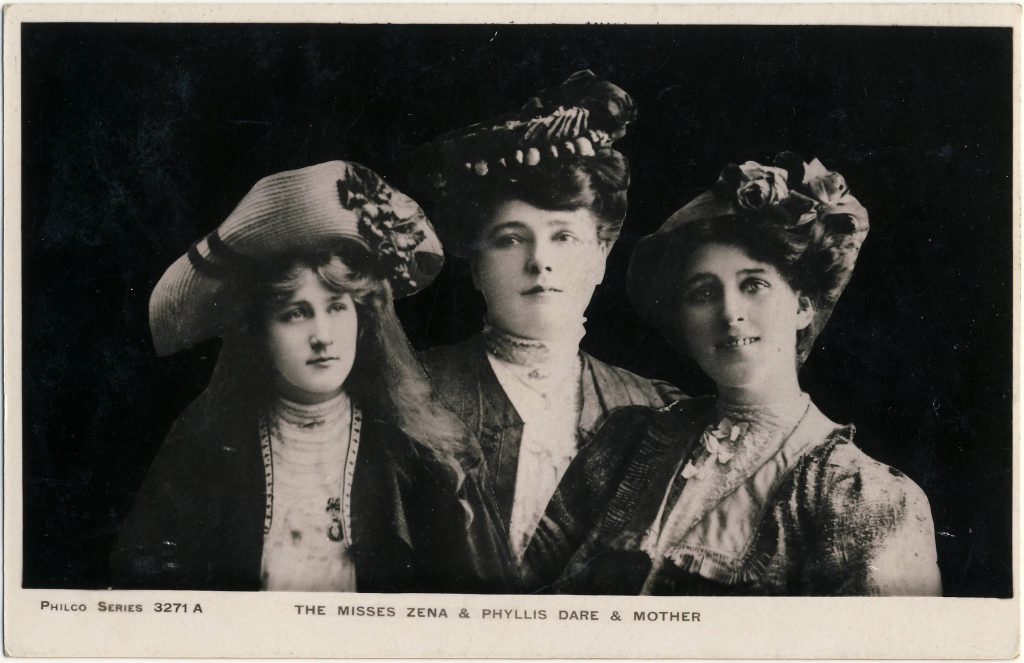

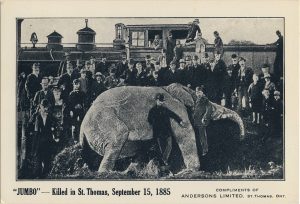

After traipsing through a whole lot of elephant lore, ringing with names like Barnum & Bailey, Ringling Bros., and Sells-Floto, the story concludes with an account of the most famous of all Canadian elephant events, the tragic

death of Jumbo at St. Thomas, Ontario, in 1885.

[2]

[2] Demise of Jumbo, 15 September 1885, commemorated in a postcard issued about 25 years after the fact

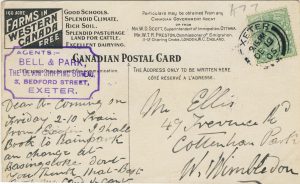

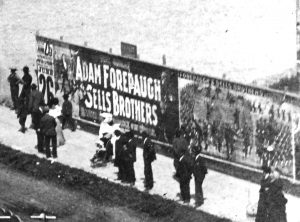

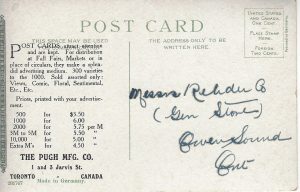

Having reflected on Jumbo’s tragic end, our readers may wish to move on to a fun story about the

backs of postcards. Backs are a side of the postcard hobby that is all too often neglected. To tell the truth, an appreciation of the postcard back is an acquired taste. But once it has taken root, an interest in the reverse sides of our cards can lead the collector in new and exciting directions. In her article about the wide array of postcard backs we saw at a “show and tell” night at the Club, the TPC’s

Barb Henderson tells a typical story,

“I will confess that until recently I was mostly a view-side collector. When another TPC member brought a mirror (cursive) writing postcard to a meeting, I decided that my novelties collection needed one of those – and so I began looking at backs trying to find one.” One interesting thing about back collecting is that, more often than not, it’s the user of the card whose written

additions to the manufactured artifact are responsible for the bulk of its current value. (TPC member

Dave Moore proves this point in a separate article in this issue.) One of Barb’s backs — with a message in Morse Code — is shown here.

[3] Writing in code was both fun

and a way to keep your message secure from the prying eyes of the Clinton, Ohio postmistress (in this case). The opportunity of discovering an interesting back like this is one reason not to neglect the “two dollar boxes” at shows. When you find a great back, you get more than two-dollars’ worth of fun before you’ve even seen the front.

[3] Postcard back-talk — in Morse Code!

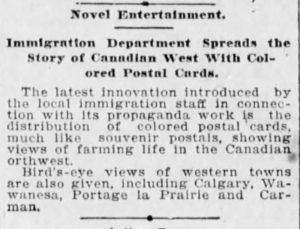

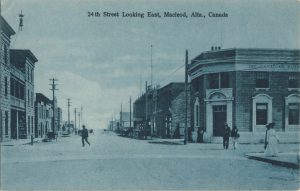

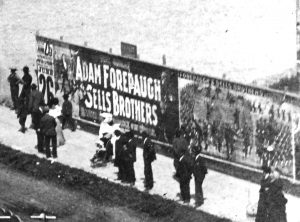

Another prized back-type (prized, at any rate, by historians of the postcard trade and its economics) is the

“sample” back, which typically includes an over-printed price list intended for small-town shopkeepers and druggists who might be persuaded to supply photos that the publisher would turn into a finished set of saleable postcard views on the stated terms. If you don’t follow that, take a look at the sample card shown here,

[4] which advertises postcards on behalf of Toronto’s

Pugh Manufacturing Co., one of the second tier of Canadian postcard publishers (in terms of output). It’s a good example because it’s addressed to a general store (operated by the Rehder family of Owen Sound, Ont.), which would have been just the sort of customer that a postcard publisher was targetting. A good many Canadian sample cards exist, and the more of them that we can collectively assemble, the more we can learn about the commercial history of Canadian postcards.

Be on the lookout!

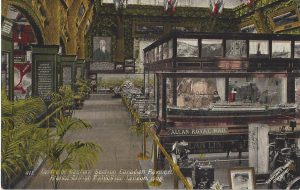

[4] Pugh Manufacturing Co. sample card

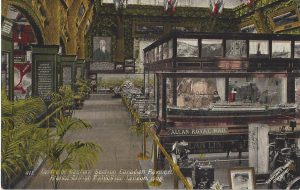

The “two dollar boxes” that were just mentioned bring us to our next Card Talk article. John Sayers of the TPC tells us in this issue about some of his “two dollar box” finds. For example, at a recent postcard sale, John found lots to interest him in the bargain bin, including a great addition to his maritime collection in the form of a Valentine & Sons (U.K.) card [5] depicting the Allan Line booth and display at the Franco-British Exhibition of 1908. This exemplifies one of the great advantages of postcards as a collectible, i.e. that there are just too many postcards, covering too many places and topics, for dealers to know infallibly what every specialist collector really values (the moral being that you can regularly leverage your specialist knowledge into great and satisfying buys). Looking at John’s Allan Line card, it’s intriguing to notice, at left, some sort of display of Canadian rotary saw-blades. More value!

[5] Franco-British Exhibition, London — The Canadian Pavilion

[6] Olympic Stadium, Berlin 1936

At another sale, the eagle-eyed John also found five cards from a series published at the

1936 Berlin Olympics. As he notes, while he doesn’t normally collect that type of thing, these came at a price that easily justified a deviation from the routine. The unused cards appear to have been part of an “official” series numbering over 100. The Olympic rings are on the reverse, along with a rubber-stamped “postmark”. One example

[6] shows the stadium that is so familiar from films and which was the scene of Jesse Owens’ famous race. As always, information from those who are specialists in the areas we discuss — in this case, the Olympic Games — is welcomed.

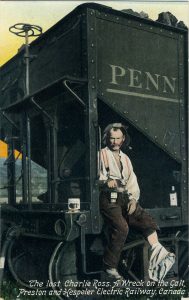

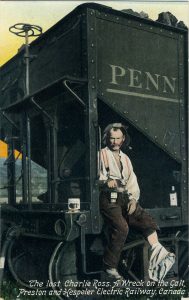

Assuming the role of postcard detective, I hunted down the story behind two fairly well-known postcards from what is now the city of Cambridge, Ontario. The cards memorably feature a hobo referred to in the cards’ captions as “the lost Charlie Ross” (see example [7]). It struck me that there just had to be an interesting story behind these deltiological oddities. My hunch was correct: the resulting article recounts the once notorious kidnapping of the four year old Charlie Ross from the front yard of his parents’ home in Germantown, Pa., on 1 July 1874. This audacious crime instantly became a cause célèbre and was followed by decades of speculation over the fate of the poor innocent lad. The number of wayward boys who were investigated as possible “Charlies” eventually climbed into the hundreds (if not thousands), with older pretenders to the throne coming forward right through the 1930s. The Cambridge “Charlie” cards are therefore examples of a North American popular culture phenomenon of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Interestingly, the well-publicized failure of Charlie’s kidnappers to recover a ransom — which happened because Charlie’s father disobeyed instructions and went to the police — was said to have brought an end to child kidnappings for ransom in the U.S. for several decades. The upshot of the story was a sad one; no trace of Charlie was ever found. While it’s unlikely that he survived for very long after the kidnapping, the whole truth about “the lost Charlie Ross” will probably never be known.

[7] The Lost Charlie Ross, a Wreck on the Galt, Preston and Hespeler Electric Railway, Canada

Finally, in the newest installment of our series “

Canada’s Postcard Photographers“, we look at the short but interesting career of Edmonton’s

Charles W. Mathers (1868-1950). In 1892, Mathers, a native of Lucknow, Ont., became the first professional photographer to install himself permanently in what was then Edmonton, N.W.T. More interested in public photography than studio portraiture, he devoted himself to recording the life and times of Edmonton, northern Alberta, western Saskatchewan and the Mackenzie district to the north (of which he was one of the best-known early photographers). Mathers produced many “stock images” of pioneer life for view books, settlement-promotion literature, and newspapers requiring illustrations for stories about the “Great North West”.

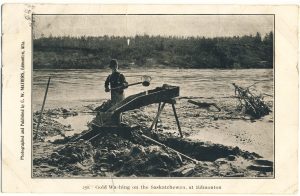

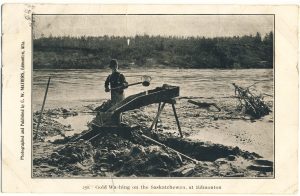

In the year 1904, as the postcard craze took off, Mathers published some of his images — it’s not clear how many — as postcards. A number of the scenes he chose were already a little dated, such as this 1893 image of a placer miner and his “grissely” (or sluice) in search of North Saskatchewan River gold [8]. While Mathers was in on the beginning of the postcard era in Edmonton, he did not stay to partake in its rapid development. Like many men of his day, Mathers was not inclined to stay long in one place, and by 1905 he had departed Edmonton for Vancouver (although he is said to have returned to photograph the celebration of Alberta’s entry into Confederation in September of that year). Shortly after the end of the First World War, Mathers and his family moved to California, where he continued his photography business, became a U.S. citizen and eventually retired in the Los Angeles area. There is no indication that he produced postcards or other “public” images at any other stage of his life, although his Edmonton and regional images continued to appear on cards produced by other publishers after he had left Alberta (whether with permission or not I do not know). As noted in the article, a number of Mathers’ postcards are included in the University of Alberta’s Peel’s Prairie Provinces website.

[8] C. W. Mathers photo (1893) published as postcard (c. 1904)

In addition to these articles, the new

Card Talk takes

a photographic look back at Toronto Postcard Club memories of the

1980s and offers our members an updated show calendar, advertisements, notes and announcements of upcoming meetings. Please consider

joining the TPC so that you can read the whole postcard story in

Card Talk and also — if you’re in the Toronto area — participate in our meetings and other activities. To top it all off, members will receive

free admission to Canada’s pre-eminent annual postcard sale.