By Andrew Cunningham

The First World War, the “war to end all wars”, got underway just as the shine was coming off the Golden Age of postcards. While wartime demand extended the postcard’s lease on life, it also changed the nature of the medium. In Canada, at least, postcards after 1913 were less apt than previously to show off the growth of the country’s towns, infrastructure and agriculture. Instead, and not unexpectedly, they dwelt more frequently on the war and its associated sentiments. Those sentiments encompassed both the public emotions of patriotism and more private feelings of estrangement and sadness — in addition to simple curiosity about what the soldier’s lives looked like. Because Great War postcards were so popular, postcard collections are often significant repositories of images of the War, including many that are unusual or unique, as well as of accounts (brief ones, of course) of the experiences of soldiers, recruits, families and friends during and after the long conflict. We were recently contacted by a representative of the Imperial War Museum, the London-based institution, which is currently attempting to record accounts of the conflict that are found on postcards. TPC members and friends who wish to contribute should see their website for details.

As Remembrance Day is approaching, I’ve assembled a number of postcards from my own collection. They reveal the war years as they appeared to the ordinary men and women of the time and cover some — but by no means all — of the range of what is available to today’s “Great War” collector:

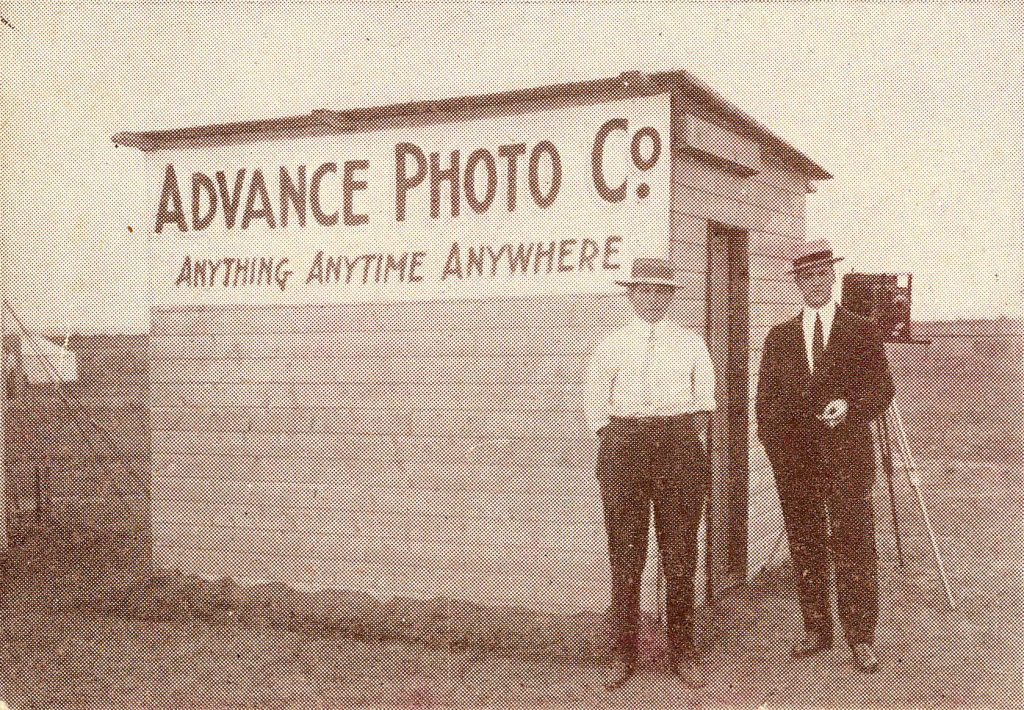

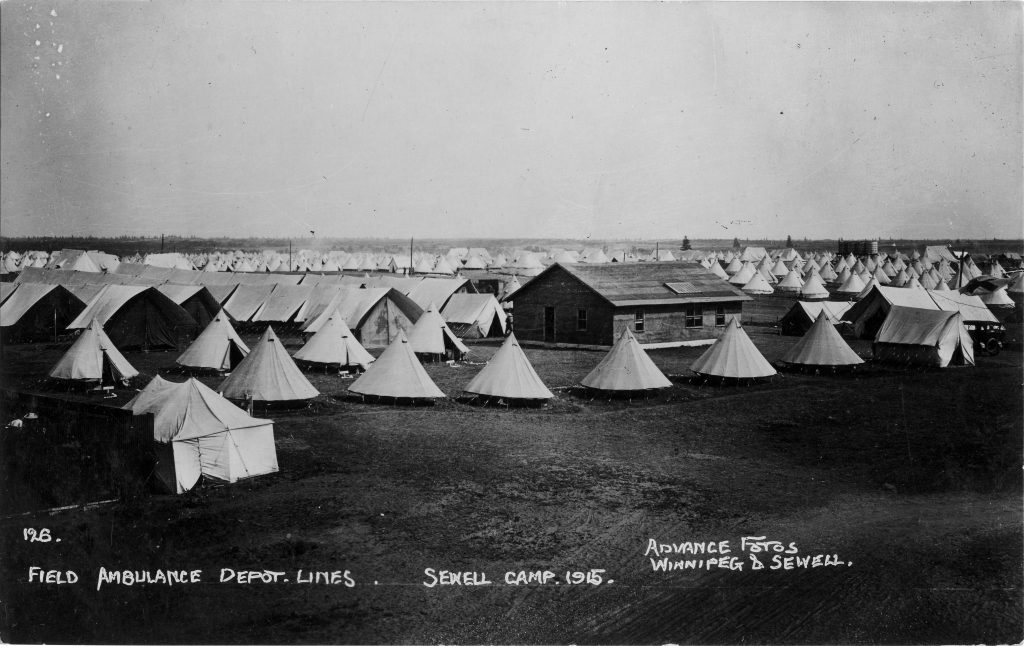

There are countless Canadian postcards depicting life at the camps at which Canadian soldiers received their pre-departure training. Among the largest of these was Camp Sewell — renamed Camp Hughes in 1915. A century later, remnants of its trenches and fixtures are discernible in farmers’ fields along the Trans-Canada Highway east of Brandon, Manitoba. As thousands of recruits passed through Camp Sewell/Camp Hughes, the Advance Photo Co. of Winnipeg was on hand to produce and sell real photo postcards depicting camp life. The number of real photo postcards produced of the camp by Advance (and a handful of other photographers) is unknown, but it is likely in the many hundreds. Despite its momentary prominence in the field of Canadian military photography, almost nothing is known about the Advance Photo Co. It had a brief existence around 1915 and 1916 and produced dozens of real photo postcards of a major flood in Winnipeg in the spring of 1916, but otherwise (it seems) almost nothing else. The company’s unidentified principals are quite possibly the gentlemen in the image below, which (more generally) illustrates how postcard photographers would have operated in such a setting.

Advance Photo Co. office (or, more likely, darkroom) at the Sewell Camp (halftone image from a view book of Camp Hughes produced by the company)

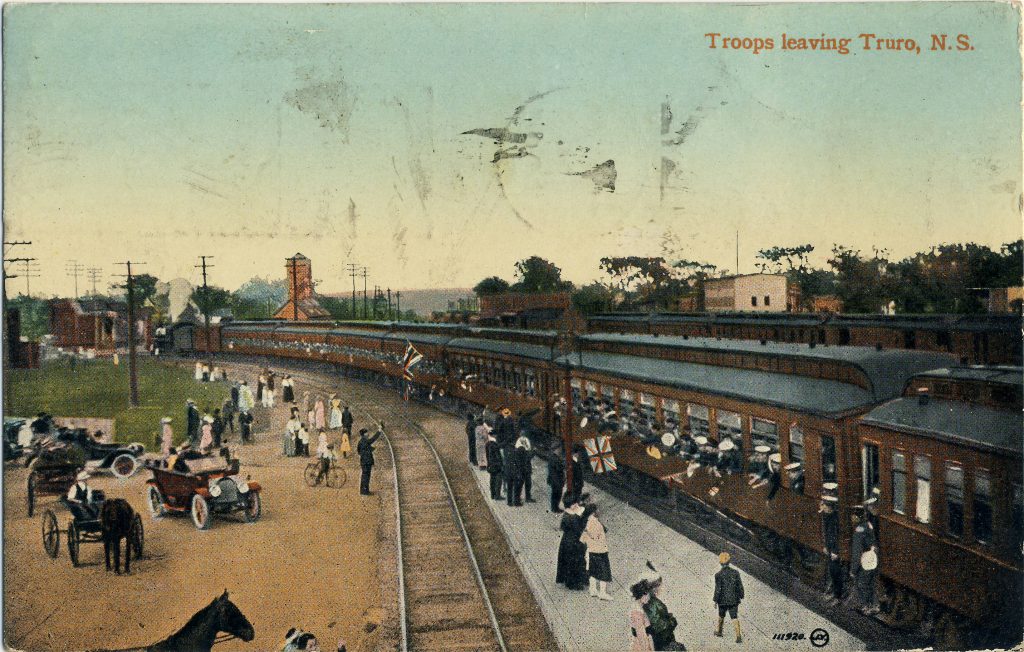

Scenes of departure are another frequently encountered World War I genre. Such postcards are usually real photos, which could be produced virtually on the spot for sale to participants in the event. But they were sometimes considered of sufficiently enduring interest to warrant production as lithographed cards. The following example — depicting the soldiers’ send-off at the Intercolonial Railway station in Truro, Nova Scotia — is by Valentine & Sons, the most prolific producers of picture postcards in Canada (and likely worldwide as well).

Valentine & Sons card no. 111,920 adds colour to a scene that we normally see only in monochromatic real photo cards.

Postcards showing such scenes only occasionally include related messages. This, fortunately, is one of the minority that does. The card turns out to have been used by a departing soldier to thank a woman who had prepared a gift packet for him. As part of the war effort, ordinary people were asked to send “care packages” to soldiers, who would then be given their names and would write them to express their appreciation. The package in this case was received by Pte. R. Grant, “C” Company of the 40th Battalion, Valcartier, Quebec, who wrote his benefactor, Mrs. Appleton P. Anderson of Sydney, C.B., as follows: “Mrs. A. P. Anderson:- I, Pte. R. Grant was the recipient of your gift on Friday night to the 40th Battalion. The boys were pleased to see the interest the women of Sydney have taken in providing for their comfort. Yours truly, Pte. R. Grant.” The rather stilted first sentence was likely dictated but the second might represent more of a personal effort.

The next thing you would have done as a soldier is to board a ship for England, and there are many postcards that depict such departures. Below is a particularly fine example – a real photo – showing soldiers waving goodbye at Saint John, N.B., as they begin the long voyage across the Atlantic. Many of them must have been imagining this moment as the beginning of a great adventure. Whether they continued to be of that view on their return (if they returned) is another matter. The ship is the Caledonia:

Transport Caledonia, leaving Saint John with the 26th Battalion and “A” Column (undated) — photo by D. Smith Reid of Saint John.

While in England, solders of the Canadian Expeditionary Force underwent additional training. Postcards were naturally a hot seller; messages to friends and family in Canada were dispatched by the thousands each day. Many of Canada’s soldiers ended up at Shorncliffe Camp in Kent (a dangerous place in its own right as it predictably attracted enemy aircraft bombardment). The postcard below shows Canadian soldiers awaiting a visit from George V:

“For Cecilie. Cecilie this is the camp where Frank Berry hung out all summer. This is the oldest camp in England. It’s the old original camp from the Beginning of history of war. The King’s favorite camp and where the burying ground [is] of all his fancy horses that die. DAD”

Once the soldiers had made their way across the channel, the most distinctive form of postcard they sent back was the “silk”, as we’ve recently discussed. This example, though showing signs of age now, is typical inasmuch as it incorporates flags and the current year into an attractive design:

These postcards, known as “silks”, were manufactured by the millions in France and Belgium for sale to soldiers.

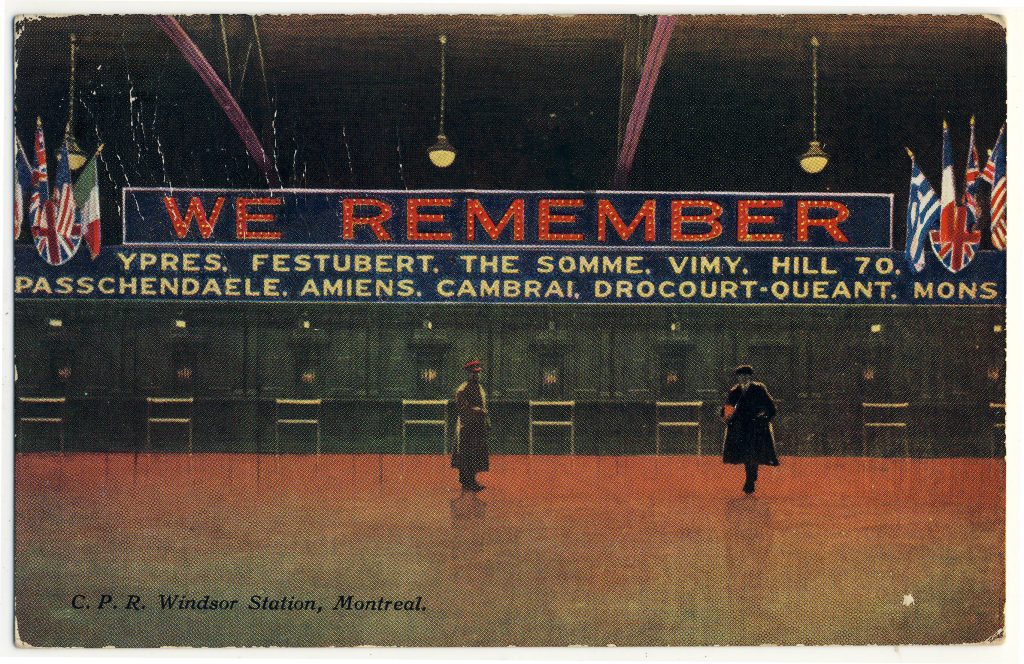

This is only a sampling of the types of Great War postcards that can be collected — there are also countless examples associated with individual regiments, real photos of soldiers, images of postwar destruction, anti-Kaiser (and pro-German) propaganda cards and many other types. The final cards, chronologically at least, are those depicting the troops’ return home and the memorials that were erected to the dead. The example below, showing the interior of Montreal’s Windsor Station, nicely combines those two elements. We see a soldier in military dress, nearly alone in the cavernous hall, overwhelmed in the image by the names of the battles in which the C.E.F. fought. Those names were already etched in the country’s consciousness when the postcard was mailed on 24 July 1919 — even though many of those who had fought in the battles were only just then making their way home.

As the Great War is now passing out of the realm of direct human memory, postcards offer us a tangible connection to the people, events and ideas that defined it.

Congratulations. This is a very interesting and informative website. I am doing some research for the penitentiary museum here in Kingston, Ontario and wondered if anyone in your club might happen to have a postcard of ‘G Company’ of the 21st Battalion Overseas Regiment taken in Kingston on Nov. 21, 1914? Here is a low resolution scan of one as found on the 21st CEF website http://21stbattalion.ca/photosdg/g_company_1914.jpg

We need to locate a higher res version in an attempt to identify one of our fallen penitentiary officers who was in that regiment in WW 1. Apparently the original that was scanned for the website has been lost. Any assistance will be greatly appreciated. Thanks.

Hi Dave

My grandfather was in the 21st, I remember trips to Kingston to visit Alf Tugwood, a comrade of his. That would have been mid 70s and I think Alf was involved with the 21st association. Anyhow, I have some copies of the 21st magazine that I will dig out to see if anything for your quest. I looked for my grandfather in your scan but couldn’t see him but hard to tell. He was Thomas Scott. On a related note, my uncle was Peter Hennessy who wrote a history of Kingston pen. The big house.