By Andrew Cunningham

Approaching early twentieth century photography from the (oblique) angle of postcards can sometimes twist the established hierarchy of photographers out of its usual shape. Many of the top photographers of the era did not sell much (or any) of their work in the form of postcards — while, conversely, the leading lights of postcard photography are often barely acknowledged outside postcard-collecting circles. So it was in the city of Winnipeg, where the iconic public photographer of the first half of the 20th century, Lewis B. Foote (1873-1957), would definitely be quite far down on anyone’s list of memorable postcard photographers. Indeed, the books that have been written on Foote’s work — including the most recent, Imagining Winnipeg (University of Manitoba Press, 2012) — mention Foote’s postcards only in passing, if at all.

As a Manitoba-focused collector, I have nonetheless discovered Foote postcards here and there, every so often, unexpectedly and always with great excitement. For perspective, there might be two or three Foote postcards for every hundred published by his equally talented Winnipeg contemporary Maurice Lyall (1887-1966), who is unknown except to a few postcard collectors and about whom no books have been published. This blog post looks at some of the Foote cards in my collection — a bit of a ragtag and random set, with the important exception of the 1919 General Strike examples.

Lewis Foote

By way of biography, L. B. Foote was a native of Foote’s Cove, a tiny outport on an island off the Burin Peninsula of Newfoundland. The standard biographical story is that he discovered a talent for photography in the 1890s, whilst on the staff of the Summerside (P.E.I.) Journal. By 1902, Foote had established himself in Winnipeg, where he was one of the busiest and best-known local photographers for nearly half a century. As noted above, he died in 1957.

Pre-Strike Postcards

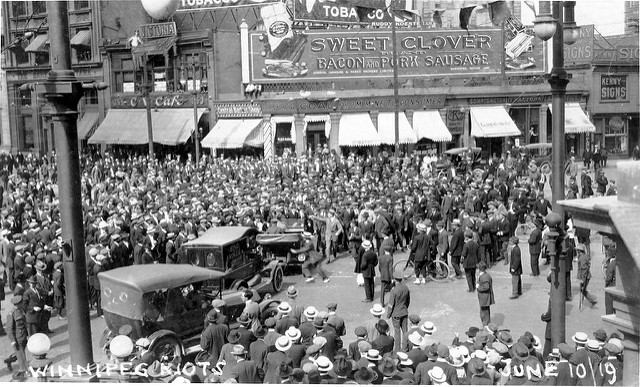

Most of Foote’s postcards are real photos (RPPCs). One exception, shown in Figure 1 below, is a promotional card (one of several, I am sure) that depicts the Winnitoba. The Winnitoba was the grandest excursion vessel on the Red River between its launching in 1909 (which is possibly when this card would have been produced) and its demise in a fire at the docks of its owner, the Hyland Navigation Co., in the autumn of 1912. Its sister ship, the Bonnitoba, which one sees much less frequently in postcards, is said to have been crushed by the river ice the following season. Hyland Park, the company-owned destination of the ships, still exists as a small public park just off Henderson Highway a little to the north of Winnipeg.

Figure 1. Forward Saloon on Hurricane Deck (Lewis B. Foote photo, published by the Hyland Navigation Co., Winnipeg, c. 1909)

While undated, Figure 2 most likely also comes from the earliest stage of Foote’s career in Winnipeg. This rather curious image of an anonymous farm family posing in the midst of a row of tall cornstalks hints at some of the whimsicality that characterized Foote’s photography throughout his career. The farmer’s fist is raised in what one imagines to have been mock triumph. Why? Was the corn perhaps the product of a good deal more effort than it was worth? Was it the farm’s first success after a string of failures? Who can say — other than that the photo illustrates, in a small way, how Foote’s images, even when they were of conventional or hackneyed subjects, often departed in small details from what convention dictated.

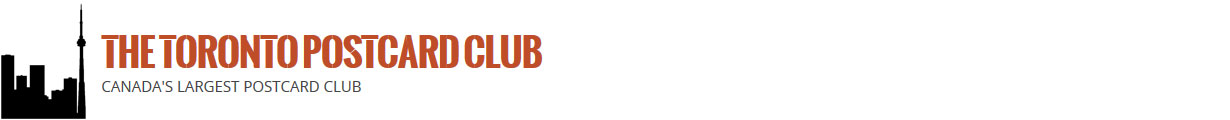

Figure 3, a rather poorly focused but nonetheless interesting image of the 1913 Labour Day parade in the town of Stonewall, Man., is an early example of Foote as recorder of labour history, an interest which (as we will see below) would just a few years later generate perhaps his greatest legacy. The sender of the Stonewall card notes the “New Town Hall” — the building built from the limestone that gave the quarrying town its name. At left, townsfolk in search of the best view stand behind a rooftop sign for “C. M. Brown – Hardware, Tinware and Stoves”.

Continuing with the theme of labour, Figure 4 shows the early stages of construction of a building near St. Mary’s Academy, the Roman Catholic girls’ school that is visible in the background. It has been suggested that the building under construction might be the H. W. Hutchinson House, 603 Wellington Crescent, now First Unitarian Universalist Church. As construction on the Hutchinson House apparently began in 1912, that thesis fits with what would superficially appear to be the age of the image on the postcard. But, having said that, many other large houses in this elegant neighbourhood would also have been under construction at roughly the same time.

In Figure 5, we have a personal postcard of two soldiers — to all appearances not young men so perhaps veterans of the Boer War or another earlier conflict. The studio blindstamp, “Foote & James”, provides a clue to the date, as Foote entered into his long-lasting partnership with George James only in 1914. So perhaps these men, despite being a little older than average, were on their way to the First World War. Their uniforms appear to this highly untrained eye to be rather distinctive — perhaps someone familiar with military uniforms of the period will be able to tell us more.

General Strike Postcards

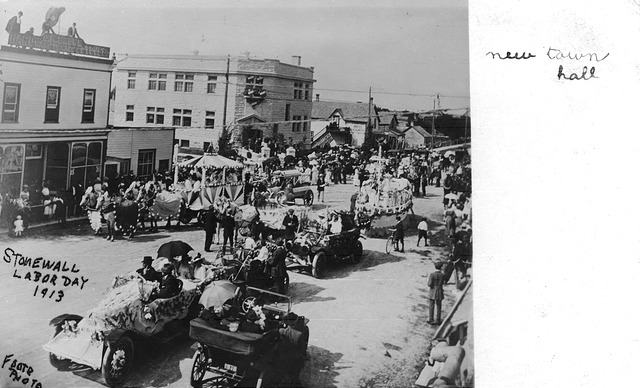

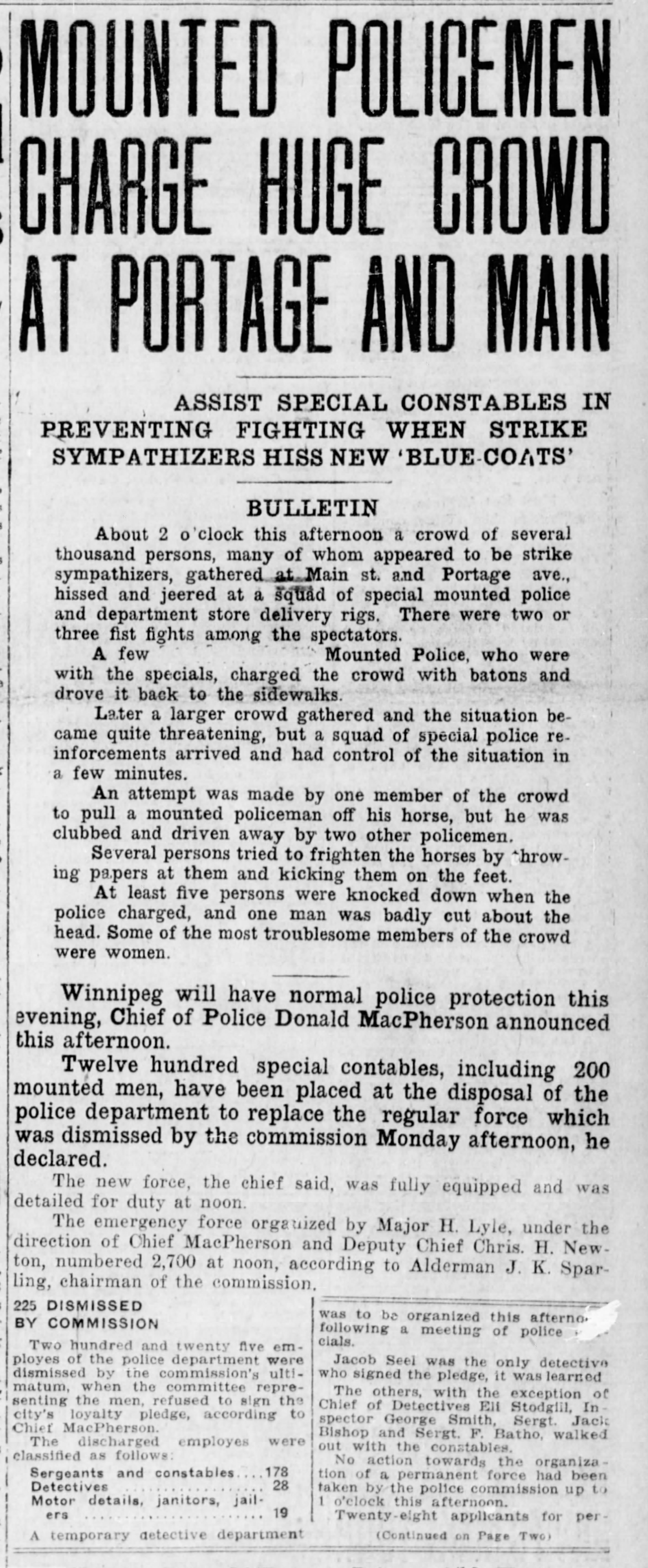

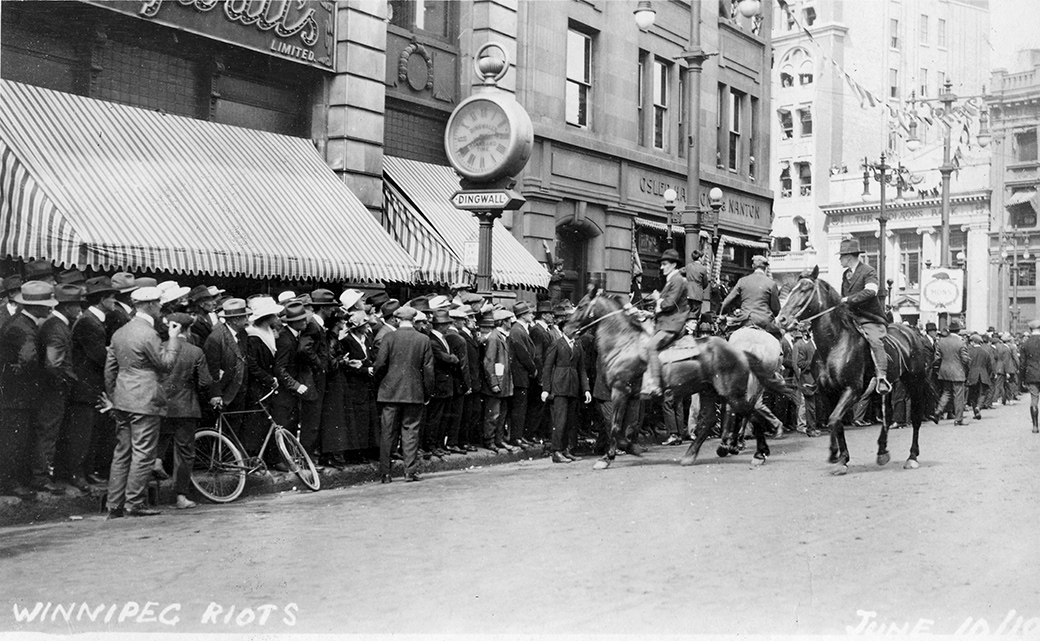

Finally, just as the soldiers were returning from the War — and definitely not unconnected with that fact — Winnipeg began to experience labour unrest. In the spring of 1919, that unrest blew up into a full-scale and at times violent General Strike. The General Strike is still arguably the most significant event in the history of Canadian labour, making headlines around the world (including the New York Times‘ famous “Bolshevism Invades Canada”) and shaped Winnipeg’s local politics for at least half a century. Foote produced photographs throughout the Strike, which lasted for a full month until called off on June 25, 1919, but the surviving photo postcards that I have seen seem to date exclusively from just two dates: June 10th and June 21st. The images below are all from the more commonly-found of the two, the 10th.

Figure 6 is one of the clearest and most interesting photo postcards of the strike, showing a large crowd at Portage & Main, with Portage Avenue East at right (in front of what is now the site of the Richardson Building). In Figure 7, a clipping from the evening edition of the Winnipeg Tribune, we learn that this melee took place at two in the afternoon — even the plight of the delivery vans that we see trapped in the crowd (including one belonging to Ringer’s, long a prominent pharmacy in the city) is noted! The timing is confirmed by Figure 8, which shows the mounted policemen in front of the McArthur Building (later the Childs Building) on the northwest corner, with a Dingwall’s Jewellers clock obligingly revealing the time to be 2:41 p.m. Between the two images, the photographer’s vantage point has shifted from an elevated position on the southwest corner to street level on Portage Avenue. If the activities in Figures 7 and 8 appear to be at least under a modicum of control, the final image (Figure 9) — taken from an elevated position above the crowd in Figure 8 — provides dramatic proof that “charge” really did mean “charge”.

Figure 7. “Mounted Policemen Charge Huge Crowd”, Winnipeg Tribune, p. 1 (June 10, 1919) CLICK TO ENLARGE

Why so rare?

Few of the Foote postcards in my collection — and none of the General Strike postcards — were postally used or written on in any way, indicating that they were probably purchased for personal albums (and as souvenirs, in the case of the strike cards). This fact may also suggest that Foote was not sufficiently invested in the postcard market to have created the necessary distribution channels for his “product” — relationships with shops, druggists and others would generally have been needed to get one’s photocards in front of the buying public. Even though more and more of the cards turn up with time, indicating that there must have been a fair number of them, I have not yet seen any single example — other than the General Strike cards and the Hyland Navigation Co. lithographs — on sale more than once. This might indicate that they were usually produced in small quantities, perhaps only at the request of individual customers for whom Foote had produced larger images. Any other examples in the collections of our members or visitors — particularly of subjects other than the General Strike — would definitely be of interest.

The only L. B. Foote postcard in the Peel Prairie Provinces collection, a group shot of the Salvation Army Citadel Silver Band, quite possibly c. 1910 as noted, may be seen here.

Figure 8. Winnipeg Riots, June 10/19 (Lewis B. Foote, 1919) Mounted policemen inspect onlookers outside the McArthur and Nanton Buildings.