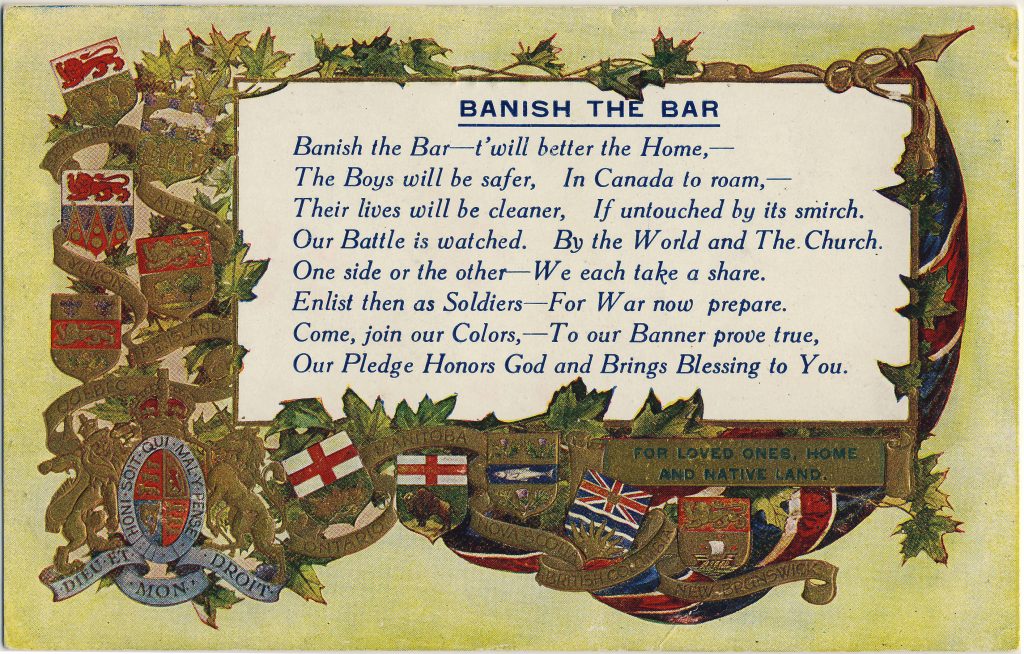

The First World War was among the first to be fought in the era of the popular song, which had been born in the music halls and came of age with the phonograph. Sentimental, romantic, humorous and religious tunes form a significant part of the war’s cultural legacy and are well known to collectors as the themes of countless series of postcards that were sent by and to the soldiers.

Typically, early twentieth-century “song” postcards were produced in series of three or four, with a different verse of a popular tune (or well-known hymn) printed and illustrated on each. The foremost publisher of these cards was Bamforth & Co. of Holmfirth in Yorkshire. This source estimates that 600 sets of song postcards were published by the company between the early 1900s and the end of the war. As the linked article notes, once war was declared, Bamforth reissued some of its song sets with new military-themed illustrations.

In this post we’ll look at four complete song sets.

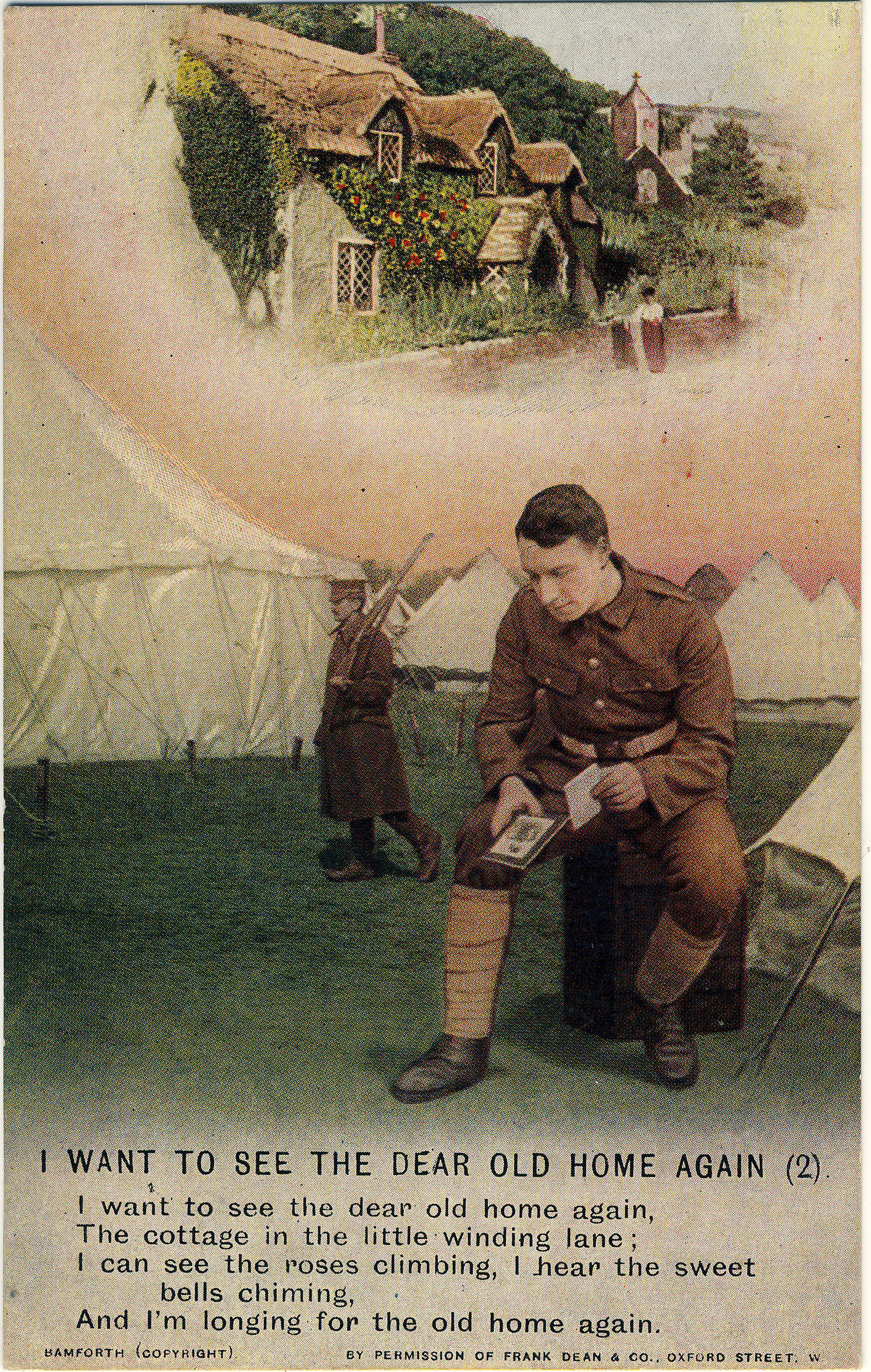

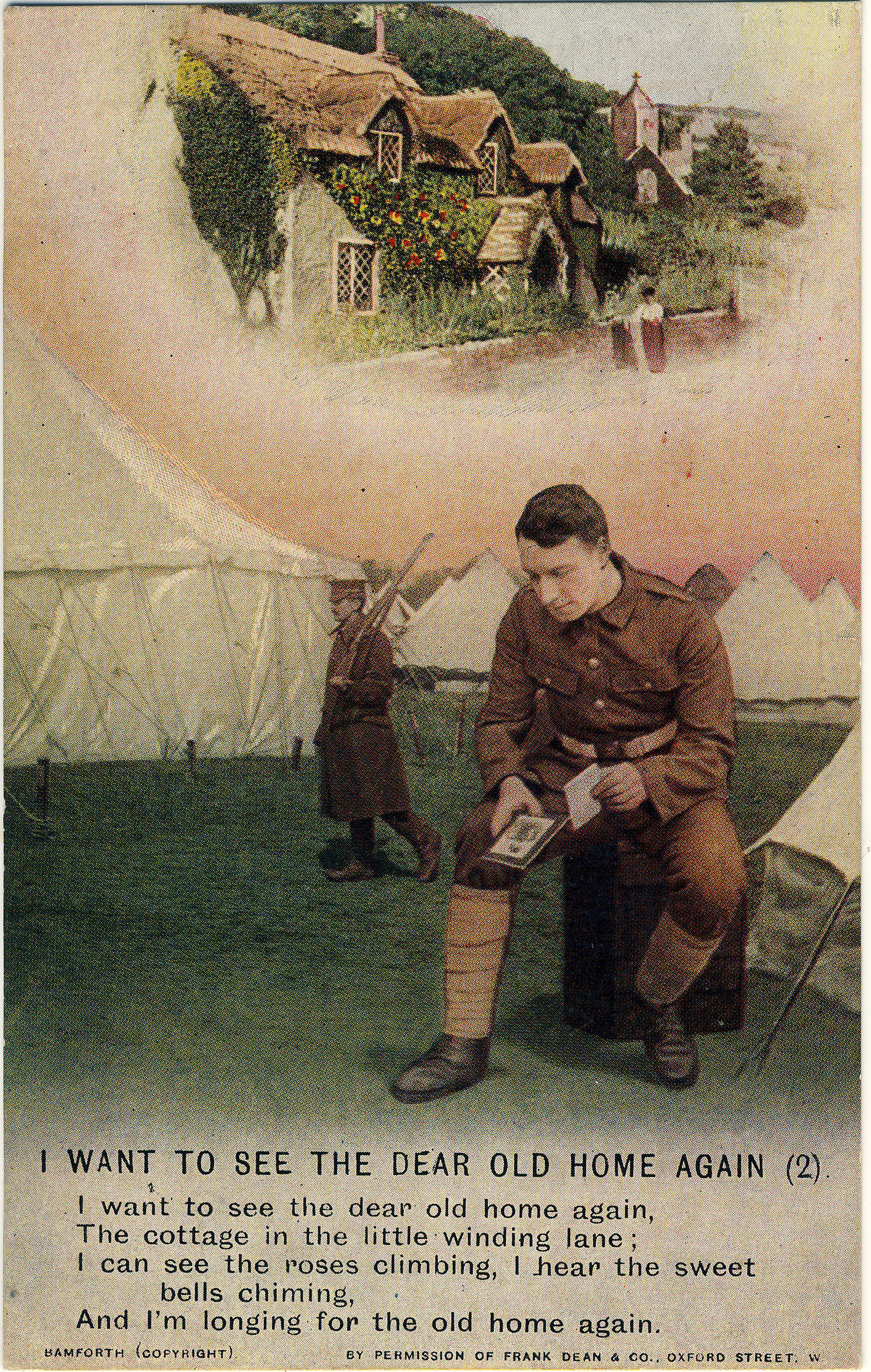

I Want To See The Dear Old Home Again

In the first scene, the soldier dreams of his home, his young children and the faithful family dog.

English village life is emphasized in the second stanza, complete with thatched cottage and chiming church bells.

Finally, with all that out of the way, we come in the third postcard to the most heartfelt loss of all, experienced most strongly when he wakes “a soldier still”.

The first song, “I Want To See The Dear Old Home Again”, dates from around the year 1900, although no recordings of it appear to be online. It was written by Frank Dean (1857-1922) under the pen-name “Harry Dacre”. Dean/Dacre is well remembered today for his 1892 composition “Daisy Bell”, one of the most enduring pieces of early popular music, with its famous refrain “But you’ll look sweet / upon the seat / of a bicycle built for two”. For its part, “I Want To See The Dear Old Home Again” is in the voice of a soldier off on some Imperial sojourn, and recounts his dreams of home and postponed love. The final line, “Then I wake — a soldier still”, would have resonated with most of the soldiers in the seemingly interminable conflict.

The three Bamforth postcards are numbered 4800/1, 2, 3 and were produced, as noted, with the permission of Frank Dean & Co. in London.

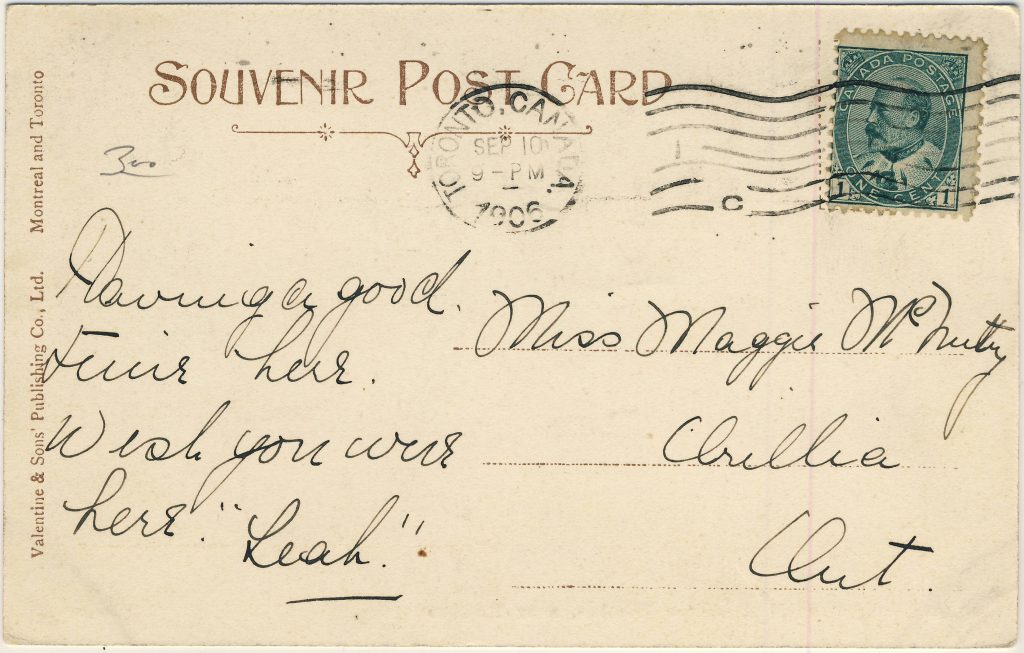

This set of postcards — like the other sets we will look at — was sent by a soldier, likely a Canadian in France. They are apparently from the First World War period although no specific mention is made of any dates or wartime events. Unfortunately, information about the soldier and his experiences was apparently left for the letters that accompanied the postcards. Without the letters, it hasn’t been possible to identify the sender.

The message the anonymous soldier has written on the backs of the three cards is as follows:

(1) This card for mother — more to follow. This card speaks my sympathy and the set will follow in future letters so be learning and singing this one till more comes; they are very nice if you … set a air at [to?] sing them by. DADIE. (2) Dear Mother, my sentiments are in this card. In my dreams I can see it all — home sweet home, but smile smile all the while — it’s some trial, but the Better will come and I’ll be going to my dear old friends at home. DADIE to MA. (3) For mother. This is the last of this series and I am a soldier still. There is more of these series. I send more for a change. Hope you enjoy my silly ways. But if I stay for years my love is for my dear old home and last of all MOTHER, only mother. From DADIE. Over the mighty deep.*

(*Note: I have added some punctuation and made other minor typographical and wording changes for the sake of clarity in the extracts from this soldier’s letters in this post. The original has virtually no punctuation, as was common in postcard messages of the day, and contains a number of abbreviations and many idiosyncratic spellings.)

Fight the Good Fight

The second Bamforth series includes four postcards, numbered 4870/1, 2, 3, 4, each illustrating a stanza of the Victorian hymn “Fight the Good Fight”, with words by the Rev. John S. B. Monsell (1811-1875), an Anglican clergyman in Ireland. The first card, shown below, depicts soldiers standing before a priest near to the front lines, as a biplane passes above them. There are explosions in the distance, presumably at the front line. These are the evidently the final words of spiritual encouragement that the men will hear before entering the fray. The remaining three cards focus on just one of the soldiers, depicted first in prayer, then in great despair, and at the last (see below), in the arms of Christ — the artist leaving it somewhat unclear whether our subject has been struck and is dying, or whether he is only in need of religious comfort on account of what he has had to endure.

The same serviceman sent the “Fight the Good Fight” set to his family, but in this case he wrote only the names of his wife and (presumably) children on the backs of the cards: “Ma” (2 cards), “Albert” and “Cecilie”.

The men at an informal service prior to entering the fight that rages behind them.

The fourth postcard, interpreting the hymn’s closing lines.

A modern interpretation of the piece, which is set to the tune “Pentecost” (1864) by William Boyd, is provided on YouTube by the choir of Brigham Young University‘s Idaho campus. A simpler version, together with the sheet music, is available via hymnal.net.

God Keep You Safe

In contrast with the previous examples, “God Keep You Safe” appears to have been composed during, and with specific reference to, the First World War. Only a little information is available online about this piece, and unfortunately there is nothing to give us an idea of how it sounded. This catalogue entry from Australia’s national archives, which presumably hold a copy of the sheet music, says that it was written by one Kate Hill Salter, with music for piano accompaniment by Edward Cuthbertson. An online catalogue that is selling a copy of the score gives the name as Kate Hitt-Salter (not “Hill”), and a check of ancestry.com does reveal an Alice K. Hitt-Salter being married to a John C. Wood in Dover in 1931. Whether “Alice K.” is Kate or a relative is hard to say, but at least we now know that there was someone with the unusual surname “Hitt-Salter” out there, even if she seems to have made no mark on history other than this half-forgotten composition (half-forgotten but for deltiology, that is!). Nothing at all turned up online for Edward Cuthbertson.

Unlike the others, this song takes the point of view of the soldier’s wife, left at home to worry about the fate of her “dear heart”, lamenting: “The hours apart from thee / Drag by on leaden, lifeless wings”. This was undoubtedly a sentiment shared by millions of family members across every one of the combatant countries. The three postcards are numbered 4960/1, 2, 3, and sport fancier lettering than is found on the other Bamforth series discussed here. Card 3 is particularly beautiful, with the soldier’s round portrait cleverly placed on the wall by the artist in place of a “thought bubble” (as appears on Card 1, also shown below).

Imagining the battlefield.

The conclusion of “God Keep You Safe”, by Kate Hitt-Salter.

The sender again writes a long letter across the backs of all three cards, concluding as follows: “This is the last series. Don’t you think it’s nice and very appropriate to its calling? I have about 30 or so of “odds and ends” cards to send anything I write on [i.e. that he can use anytime he needs to write something]. The cards can be raffled off. These cards have come from all across the Dominion — a very large collection.”

Little Grey Home in the West

The final song set consists in four cards illustrating the ballad, “Little Grey Home in the West”. Of the songs presented here, “Little Grey Home” has the most tenuous thematic connection with war. It’s really just a sentimental piece. The lyrics were by one D. Eardley-Wilmot (a member, it appears, of an aristocratic family by that name but about whom little else is known), with the tune by the famous British composer Hermann Lohr (1871-1943). Recorded as early as 1912 by Peter Dawson (and also by John McCormack and others) it appears in newspapers across North America and the U.K. as a massively popular recital piece in 1914 and afterward. The Dawson version as it appears on YouTube uses the four Bamforth postcards as illustrations. Since the song isn’t really about a soldier, the illustrations on the cards simply show the soldier thinking of the sentimental scenes that the song recalls. Much like “I Want To See The Dear Old Home Again”, “Little Grey Home in the West” works its way up to the thing the singer misses most: his true love — or, here, “the two eyes that shine just because they are mine”.

There are lips I am burning to kiss … And a thousand things other men miss.

The fourth and final card in Bamforth series 4871.

Card no. 3 seems to have hit home with our anonymous soldier, who writes on the back: “Dear Mother, This shows the mental telephone working between the soldier and the friends at home and the other thousand things he misses, but we must all keep smiling — no coldness out here –, and our wives at home and everybody smile. There is no use getting disordered as it is no use and only makes matters worse, don’t you think so? DAD”

Not all soldiers were quite so enthralled by the sometimes mawkish sensibilities of the songs. Parodic revisions of lyrics were common as the Great War servicemen creatively attempted to “keep everyone smiling”. On 22 April 1915, the Montreal Gazette reported on a version of “Little Grey Home” of which the librettist was a Captain Frost of the 14th Montreal Battalion. In his possibly somewhat more realistic take, the song went as follows:

There’s a little wet home in the trench,

That the rain storms continually drench,

There’s a dead cow close by,

With her heels in the sky,

And she gives off a beautiful stench.

Underneath us in place of a floor,

There’s a mess of cold mud and some straw,

And Jack Johnsons tear,

Through the rain-sodden air,

O’er my little wet home in the trench.

(Andrew Cunningham)